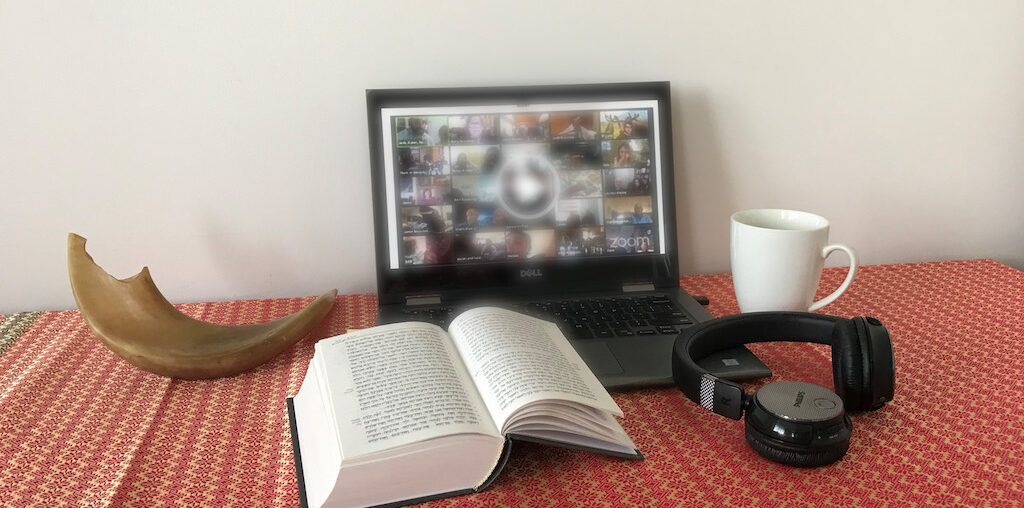

As the High Holidays approach amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, a pervasive question is mounting: how we will ‘do’ the services? For many congregations this will likely involve live-streamed events to mark the occasion in some way. Some communities are already running regular Shabbat services via Zoom, successfully engaging people in a virtual Jewish environment. Granted, it is not the same as attending synagogue in person, but it provides familiar comfort during this time of isolation.

For many in our community, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur via Zoom is not a not a viable option. Orthodox synagogues cannot offer nor partake in these virtual services as it violates the prohibition of ‘work’ on Yom Tov. To even consider using such technology is heading down the slippery slope of Reform Judaism. In Orthodoxy, taking the most convenient or seemingly logical road is not always the ‘right’ road. For these communities, prayer and other rituals including Shofar, will revert to a solitary practice for the time being. Halachah (Jewish law) certainly allows for this, and the pomp and ceremony of a crowd is not necessary to fulfill the obligations of the day. It is not ideal, but after all, the introspection that characterises this auspicious time is an individual pursuit that can be undertaken anywhere. It is something to admire, that for Orthodox Jews religion goes beyond synagogue attendance. So a virus that demands distance does not significantly impede their ongoing observance and relationship with God.

But while Orthodox Jews can rationalise their position, with virtual services not even on their radar, another segment of the community is being overlooked. Many are precluded from organised High Holiday services, not because they object to using Zoom on Yom Tov, but due to their formal association with Orthodoxy.

A large proportion of the Melbourne Jewish community self-identify as ‘traditional Jews’. They are sometimes described as ‘non-practicing Orthodox’ – they do not consider themselves ‘religious’ but are still members of an Orthodox synagogue. This is remarkably common in Australia. Synagogue affiliation is not necessarily a choice, but often a default position, usually out of loyalty to parents or grandparents. There may also be a genuine allegiance to Orthodoxy as an outward expression of one’s commitment to preserve tradition in a post-holocaust era. This phenomenon is not as apparent abroad; in places like America people seek a denomination that actually aligns with their theology and lifestyle. Reform Jews belong to Reform shuls, Conservative Jews to Conservative shuls, Humanistic Jews to Humanistic shuls etc. Similarly, Orthodox shuls are generally filled with people who are Orthodox or religiously observant to some degree. With that, there is less likelihood for tension between what members want and what their institution provides.

Traditional Jews have managed to harmonise their secularism with the Orthodox principles of their beloved synagogue. The incongruence is there, but it is mild and remains subconscious. Families drive to shul with an understanding of “don’t ask, don’t tell”, as the men scramble to find their unused kippot. Women wear their skirts and obligingly retreat to the ladies’ section ‘out of respect’, although they would never accept such constraints outside the synagogue walls. Prayers are chanted with little understanding or emotional impact, but everyone goes along with it. The rising background chatter during Torah reading has become standard decorum. The highly anticipated Rabbi’s speech helps bridge the gap between the laity of congregants and the religious proceedings. Nevertheless, for the traditional Jew, upholding the Orthodox standard is part-and-parcel of membership therein. It conjures an odd fusion of pride and imposition, but somehow it seems to work for all parties involved.

These experiences may be a form of cognitive dissonance – when one holds a set of values or beliefs, yet does or accepts an action that contradicts those values or beliefs. The matter of (not) live-streaming High Holiday services may be another such area of dissonance. Traditional Jews themselves would likely be in favour of Zoom services, but they are beholden to a ‘system’ that is insufficiently malleable for such overt adaptation. This will be accepted as just another one of those necessary inconveniences that comes with belonging to an Orthodox synagogue. Many will be content with the other virtual programs on offer (Pre and Post Yom Tov) which may in fact prove to be more inspiring than conventional services anyway. Some might be unfazed by the situation, happy to just give it all a miss this year. Others may be compelled to try something new and join a Zoom service with a different congregation on the actual festival days. Regardless of their choices, it still begs the question: how is it possible that something that is ordinarily deemed the highlight of the year is suddenly sidelined in the name of tradition? It seems counter-intuitive to dismiss an opportunity for Jewish engagement on the premise of Jewish law.

Traditional Jews will openly concede that their synagogue attendance has little to do with prayer and everything to do with people. Their primary motivation is not belief, worship or obligation; but rather culture, community and connection. Some might scoff at this as being shallow and inauthentic, but this form of Jewish identity is entirely legitimate and meaningful. For many traditional Jews, the absence of High Holiday services will leave a gaping hole their religious affirmation. They do not have intrinsic capacity to relegate prayers to private spaces, like their Orthodox counterparts. The obvious alternative is to participate in a virtual service, run by their their own synagogue with fellow congregants – but this option is not available to them. In effect, the nature of their religious identity is being repudiated by the very institutions to which they belong.

All synagogues are floundering under the current restrictions, and many Jews are feeling the void of not being able to fully connect with their communities. For some however, that frustration is exacerbated when a remedy seems entirely plausible, yet is so inaccessible. The discourse around live- streaming on High Holidays may be novel, but it is a familiar narrative. It invites us to consider the impasse of sanctioning doctrine over ideals. Perhaps this is an opportune time to reflect on our synagogue affiliations and how much dissonance we bring in to our Jewish identity.

Comments are closed.