Passover will not completely pass over us this year. As we were only three weeks into the reality of the pandemic when we observed Passover last year, my husband Larry and I had a small, quiet, seder for two. On March 27, we will at least share a virtual Zoom seder with members of our synagogue.

My husband Larry and I have been fortunate. As were our Hebrew ancestors, our family and circle of friends have been spared the “angel of death” in that we lost no one to this (God willing) once in a lifetime scourge. Friends who contracted the illness have survived, albeit with some lingering effects that we hope and pray will result in a r’fuah sh’leimah, a complete recovery.

Despite my gratitude, I was feeling that more than Passover had passed us by. I know I share the feelings of so many others that we have lost a year of our lives.We not only missed out on life events—first birthday parties, bar mitzvahs, weddings, graduations, funerals. We also had lost out on the small things: a restaurant dinner with friends; a movie or play, a live sporting event, a simple hug from a friend.

This feeling of ennui especially hit me when February arrived. Physically, I was doing fine. But emotionally, I felt sad and cold and dark. Would this pandemic ever end? Would we be able to travel to see our children and grandchildren this summer? When would the world begin to turn to normal?

In the middle of all this, I was working on my third book. Fradel’s Stories, a compilation of essays my mother had written in the last five years of her long life as well as articles I had written about both my parents and my siblings. After hours and hours of organizing, editing, and re-editing, what should have been a labor of love was turning into just labor. Of course, that put more pressure on me, something that I certainly didn’t need in my emotionally depleted state.

On the third Saturday in February, I resumed my editing with “My Romance,” my mother’s description of her failed romances with men she had she dated while living and working in New York City in the 1930’s.“The saying goes, ‘You have to kiss many frogs until you meet your true love,’” she wrote. “ Well, I knew many frogs.”

All that changed when she was introduced to Bill Cohen, her brother and her cousin’s co-worker in an Upstate New York clothing store. After a whirlwind three month courtship, my father proposed over ice cream on February 14, 1940. “We had just seen Gone With the Wind,” Mom wrote. “Bill must have thought I was Scarlett O’Hara, and I must have thought he was Rhett Butler. I said yes.”

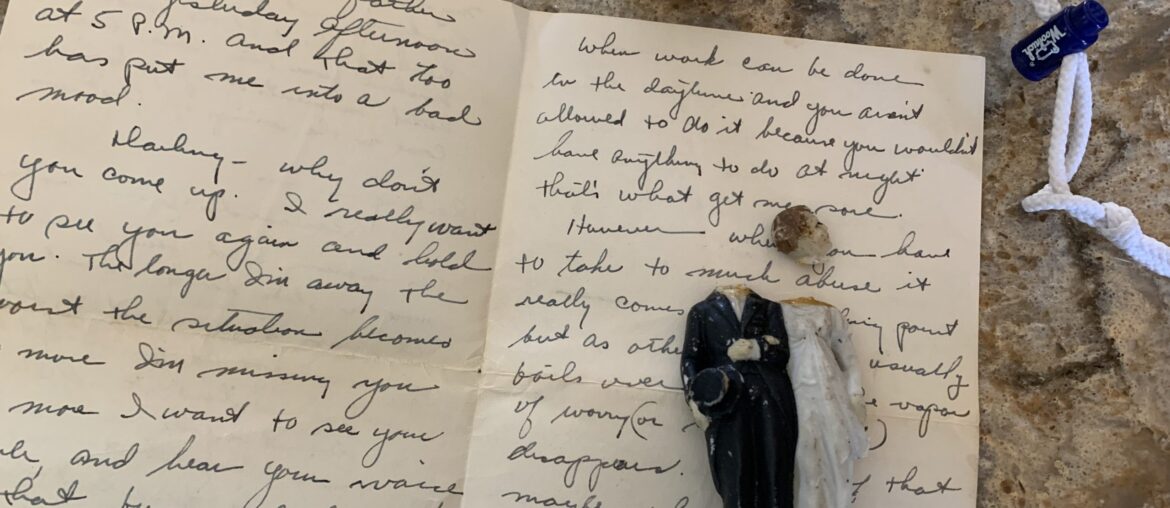

Over the next six months, they maintained a long-distance romance, seeing each other infrequently but writing often. Mom had kept the letters in her dresser her entire life.“Where are those love letters now?” I thought. Then I remembered that they were in a metal box that held all my treasured correspondences, exactly where I had put them soon after her passing.

Even though I had been known about them for at least sixty years, I had never actually read their love letters until that Saturday morning. My father spoke of his loneliness, his love (mixed in with some bad poetry), and his excitement about their pending marriage. My mom’s letters shared some of his romantic sentiments, but she, always the practical one, also detailed the wedding preparations along with constant reminders for Bill to get the necessary medical tests before the August 20, 1940, ceremony.

After reading them all, I called all three siblings to share the emotional news of my find. That triggered more memories, more family stories. Laura reminisced how her eight-year-old self had found our parents’ love letters and decided to play post office by delivering them to each of the mailboxes on our street. Jay remembered how, while living in that same Upstate New York house, he and a fellow five year old called the fire department to report a “blaze” so the two of them could get a first hand look at the town’s new fire engine. Bobbie retrieved another letter—the one my parents had written to her in 1977 when, as a recent college graduate, she was struggling to find a job.

After my phone calls, I went back to the kitchen table to resume work on my book, but I was no longer alone. I felt my parents’ strong presence, surrounding me with encouragement to keep writing and with quiet assurance that—as they had done as members of the Greatest Generation—we too will survive this challenge.

On March 2, the tenth anniversary of my mother’s passing, I sent my manuscript to my editor. Months of work are still ahead: more editing, picture placements, cover design. But I am confident that on or near August 20, what would have been my parents’ 81st anniversary, Fradel’s Stories will be launched on Amazon.

Soon, I will give my house a thorough cleaning, make my chicken soup and matzoh balls, chop up my apples and nuts for the charotzes, and set our table for our Zoom seder. With all the recent good news of the medical front, I have faith that next year’s seder will be a more crowded, joyous, affair. Thanks to the love and memories my parents and siblings have shared with me, the fog has lifted. Chag Sameach!

Comments are closed.