A new museum opened in Paris last week: Maison Gainsbourg, the home of Serge Gainsbourg which his daughter Charlotte has preserved intact since Serge died in 1991. Attached to the house is a separate curated museum, dedicated to this revered – in France – poet/singer/songwriter. The house is very personal to Charlotte, filled with objects that felt almost sacred to her in her childhood. They were so important to her father that she didn’t dare touch them and they have a very private meaning for her.

The house was also a refuge for Charlotte in her grief after her father died; she couldn’t go to the cemetery where her father was buried because it was overrun with fans.

But as the house will now be open to the public, everything in it will develop new meanings for those who visit the house and the museum.

Charlotte’s memories and place of personal recollection will now become everyone’s property.

In a few minutes, we will recite the Yizkor prayer. In a sort of reversal of Charlotte Gainsbourg’s experience of the private becoming public, the YN reckoning – which is all about the collective [ashamnu, bagadnu] – will now become especially personal, the central Yizkor prayers being said for individuals’ parents and other close relatives.

As a prayer, Yizkor first emerged in the Rhineland in the 12th century, following the first crusades and the associated martyrdom. It spread very quickly to all the Ashkenazi world and to Italy and it influenced the Sephardi world. Benjamin Sommer (historian and theologian), to whom I am especially indebted for his lecture on the origins of the Yizkor prayer, posits that this popular custom is in fact much older than 12th century – or at least that the idea behind it goes back much further, which is why it was so quickly adopted.

The prayer begins “Yizkor Elohim”. We are asking God to be “zokher” of our parents or of the name of our parents.

At the root of the opening of this prayer is the word with the Hebrew shoresh Z.Ch.R – zachar, zocher, Zecher. Those who know some Hebrew know that this means “remember” or “memory”.

Scholars tell us that at its heart, zekher means not only memory, but also “to name” or “the name of”. “Zakhor” is not only to remember, but also to name, to utter the name of something.

And in ancient tradition, the uttering of the name of something makes the thing real. To name something is to declare its essence and make it present. When, in the Yizkor prayer, we ask God to “zokher” someone, we are asking the Divine to utter the name, because to utter the name is to make the person present.

Benjamin Sommer tells us that this comes from ideas about the afterlife in the ancient near east … the idea that there is life after death but it’s precarious. And in the ancient tradition, if you have children who ensure you are remembered, you will have a good afterlife.

And whatever we think of the afterlife, we know that when we speak of the dead, we are keeping the person alive in an almost visceral way. We are reminded of the saying that a person dies a second death when they are no longer remembered in the world. Anyone who has seen the Pixar movie Coco knows that the Dia de los Muertos, widely celebrated in Mexico, is a tradition based on this idea: as long as there is someone to remember them in the Land of the Living, the dead are not really dead.

Rabbi Yohanan in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Yohai teaches that each time we state an insight in the name of the teacher, the teacher’s lips vibrate from the grave [Talmud, Yevamot, 97a]. They live on.

We say their names and we remember them; by uttering their names, we make them present.

And while the Yizkor prayer asks God to remember those who have passed, when we begin to recite Yizkor, our hearts open with how we remember them. What we remember may shift over time. It may be a name. Or a face. Or a flash, a glimpse of the person. Or it may be something more abstract, more emotional. The feeling of having them here beside us in the world, of being sort of behind us, above us, perhaps beside us in shul.

Many of us have strong childhood memories of shul on the High Holidays. Those foundational memories often encapsulate family relations and might also form a kind of personal theology

In a touching story from her own childhood, Sara Horowitz has described just such a memory. She is standing next to her mother, who turns for a moment from her mahzor to whisper, “Bubbe always cried when she read this.” The chazzan has just uttered a line that is adapted from Tehillim [(Psalms) 39:9] ‘Al tashlicheinu le’et zikna kikhlot kocheinu ‘al ta’azveinu—Do not abandon us in old age, when our strength has ebbed, don’t forsake us. Sara’s mother was tapping into her own childhood memories, bringing an image of Sara’s bubbe as the mother of a young child into the sacred space of their prayer. Her bubbe, suffering from dementia, no longer prayed with them.

Each year, for as long as Sara and her mother prayed side by side on the High Holydays, her mother would repeat her comment. It was as though her mother’s reflection on the mahzor was codified into the Yom Kippur liturgy. Al tashlicheinu l’eit zikna—Do not abandon us in old age: the verse is repeated four times in the Yom Kippur liturgy. To this day, Sara cannot recite the verse without thinking of her bubbe, … and of her mother remembering her bubbe.

When we say Yizkor, some of you will leave the shul, holding to the minhag that one remain in shul ONLY if one has lost a parent. This was not my minhag. As an adult, I have always stayed in shul for Yizkor even though until 6 years ago both my parents were alive. But I always felt I had people to remember: a schoolfriend who died tragically in childbirth more than 30 years ago, as well as uncles and grandparents and extended family. Family who died well before I was born, family I never knew, but family that I remember anyway.

It’s a strange notion to remember someone or something that we never knew.

But an idea that suffuses our tradition. The Hebrew word — zachor — is repeated more than 150 times in the Tanakh, with both Israel and God commanded to remember: to remember the Sabbath, to remember the covenant, to remember the exodus from Egypt, to remember Amalek.

In his masterwork on the subject of memory, “Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory”, the historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi writes that Jewish memory is a fusion of past and present. It is not just a recollection of the past that keeps a sense of distance, but it is a re-actualisation, a means to act in the present. We bring into being the very thing we remember.

Jonathan Safran Foer writes that Jews have six senses, not five, the sixth being memory. In Everything is Illuminated he reflects that others:

use memory only as a second-order means of interpreting events, but for Jews memory is no less primary than the prick of a pin, or its silver glimmer, or the taste of the blood it pulls from the finger. The Jew is pricked by a pin and remembers other pins. It is only by tracing the pinprick back to other pinpricks – when his mother tried to fix his sleeve while his arm was still in it, when his grandfather’s fingers fell asleep from stroking his great-grandfather’s damp forehead, when Abraham tested the knife point to be sure Isaac would feel no pain – that the Jew is able to know why it hurts.

When a Jew encounters a pin, the Jew asks: What does it remember like?”

In my personal moments of remembering those I never knew, I think not only of them but of a world that was lost, of those that lived and worked and loved and despaired and hoped and cried and talked – mostly in Yiddish. I imagine another universe. I imagine, without even beginning to comprehend, how my vanished grandparents might have felt going to certain death, but at least believing that their 4 children, of whom my father at 15 was the youngest, were safe. [They are all gone, those 4 children: 2 who did not live out the limit of their days, lo b’kitzam, and 2 b’kitzam, the 4 resting on 4 different continents.]

And if remembering people and places and events we never knew or experienced is powerful, how much more so remembering those we did know.

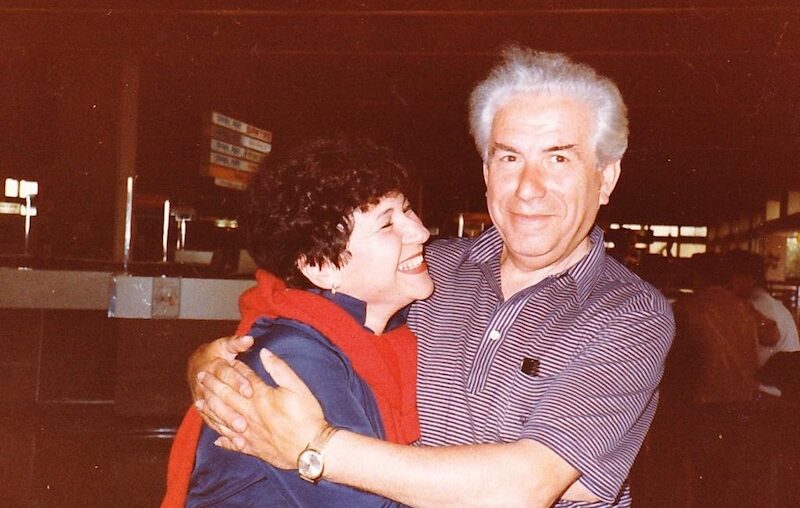

This particular year, my year of kaddish for my mother, how do I sit in this shul and not feel in every part of me her presence beside me, her reading the prayer for Australia or the prayer for peace as if they were theatre pieces. Sharing a smile with her, a joke, a laugh, a song, a hug. Appreciating the beautiful voices of the chazzanim and the wisdom of other people’s drashas. Sharing naches from her grandchildren, my children. Her invisible presence is palpable to me this year and I suspect for all the years to come.

How do I stand in this community and not feel the aching absence of Mark Baker – remember him and his passion for this shul, and my own connection with him, going back to my teens. Mark, who stood here last Kol Nidre, holding the Baker family sefer Torah, as his wife Michelle did last night. Mark, just a year ago, aware that like his first wife Kerryn and his brother Jonny, he would probably not live out the limit of his days, his would be lo b’kitzo. I remember him and he is present for me, sitting on the other side of the mechitza smiling at me. I see Nitty and remember her brother Gersh, taken far too soon – most definitely not b’kitzo, and the gaping hole in the lives of the Rapke family and Gersh’s whole community; I see Lindy and her family and in them and in the art, I feel Melma’s presence. I look at Rochelle who just a few short months ago participated in our tikkun leil with her husband John Umansky in the audience, supporting her with pride, before the family was blindsided by John’s sudden death. I think also of the Sharp, Milner, Schneeweiss, Shroot, Mittelberg, Ben-Moshe and Sifris-Ross families, and I know that they too are learning to live in this world without a loved one.

For others, the losses may have been less public – but are no less painful.

And, for many of us, the loss may have been years ago, but we think of our departed parents or other loved ones and feel time collapse, as we recall glimpses, feelings, expressions. We conjure them up and make their presence real.

It is many years since my bubbe and zaide died, both well advanced in years, the pair who courageously handed their young daughters to strangers, trusting in them to protect their children in the darkest of times, who brought their fiery love of Yiddish and family to this old-new place with its own hidden troubled past. I remember them and I think of the large, loving family we have become. For decades now, I have conjured up those grandparents at Yizkor in my personal rememberings. In recent years, I have sadly added beloved aunts and uncles and 5 years ago, my own precious father.

“Our bereavements are achingly personal but all humankind knows loss.” [Sara Horowitz] So we will stand together at Yizkor to ask that God remember the spirit (or soul or breath or life) – the neshama of the departed. We will feel their absence, but in calling on God to remember them, to name them, and in naming them ourselves, we will make them present – each of us, in our own personal way.