In The Tragedy of Hamlet, Shakespeare, using the Prince of Denmark as his mouthpiece, articulates that the purpose of theatre is “to hold, as ‘twere, the mirror up to nature’’ since drama should ideally present a form of truth (Shakespeare Hamlet 3.2 20). However, I am disheartened to see art imitating life so much as I navigate my way through the muddy waters of The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare’s complex Problem Play, with my current cohort of high school students. Sadly, The Merchant of Venice has never felt so emotional, so timely and so real to all of us with ties to the Jewish Community.

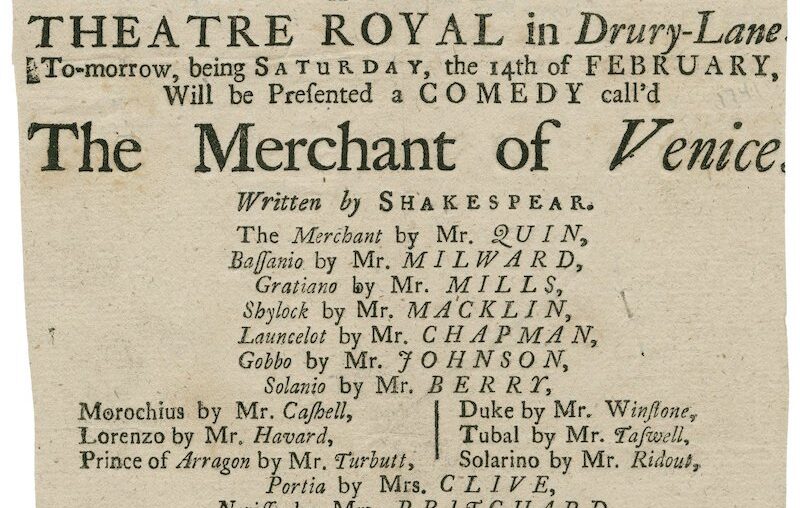

I first encountered Shakespeare’s controversial text in my public high school and then revisited it in university in an upper level seminar course on Renaissance Drama. Currently, I teach the play to grade 9 students in a Jewish Private High School as part of the English curriculum’s Shakespeare unit. I continue to be fascinated by the infamous Shylock who is depicted as both victim and villain. In fact, most of the play’s characters are portrayed as extremely flawed and unlikeable and Shakespeare skillfully conveys the moral ambiguity of all humans. A more nuanced reading of this classic “Comedy” reveals that everyone, irrespective of race and religion, must learn to become more compassionate, socially responsible and humane.

When I introduced The Merchant of Venice last year, in the Fall of 2023, everything felt quite predictable. We began with a taste of Shakespeare’s London and a glimpse into the History of European Jewry. We discussed the stereotypical theatrical convention of “The Stage Jew” and we spoke about the folklore that most likely influenced Shakespeare’s perception of Jews, since there were, most likely, no Jews living visibly as Jews in England during Shakespeare’s time. (In 1290, all Jews were expelled from England by King Edward I; they were not allowed to return until 1655). My students understood the historical context in which the play was written and were ready to tackle its mature concepts and themes.

And then, the October 7 Hamas terror attack on Israel occurred and its unrelenting aftermath. Consequently, pretty much everything I was covering curriculum wise felt trivial, except the teaching of this play. Sensing its relevance, the students were more engaged than ever before. Unexpectedly, despite 20 years of experience teaching the Bard’s brilliant works, I was not prepared for the emotional impact of his harrowing words.

It is true that I almost burst into tears when reading the passage aloud where Shylock, the Jewish moneylender, attempts to articulate his conflicted feelings about doing business with Antonio, an antisemitic Merchant: “Signor Antonio, many a time and oft/ In the Rialto you have rated me/ about my moneys and my usances:/ Still have I borne it with a patient shrug,/ for sufferance is the badge of all our tribe. /You call me misbeliever, cut -throat dog,/ and spit upon my Jewish gaberdine…” (Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice 1.3 102-108). Antonio does not deny any of this. In fact, he informs Shylock that they need to do business as enemies and not friends since he is “like to call thee so again, /To spit on thee again, to spurn thee too” (1.3 127-128). It is a horrible display of hurtful antisemitic behaviour and it is heartbreaking. Shylock admits that he has put up with the hatred passively and that he has grown accustomed to it, but we can also see that it is crushing his soul. Shylock, who already feels excluded because his strict observance of the Kosher dietary laws prevents him from dining with the Christians, is forced to realise that the antisemitism will be ongoing; as long as he lives in Venice, Antonio will continue to spit on his beard and his clothes. When Shylock later breaks into his “Hath not a Jew eyes?” (3.1 54) Human Rights monologue, where he asserts his dignity, it is impossible not to feel moved. Even the taunting antisemitic Solario and Solanio, who prompted this speech, are jaw droppingly silent.

Shylock is a broken human who feels compelled to unacceptable conduct. In his final scene, after he is forced to convert to Christianity, because the Christians believe it will save his soul, Shylock is ostracised by both Christians and Jews alike. He has nowhere to turn. No community will forgive and accept him. It is sickness unto death. “I am not well” (4.1 394), he mutters, as he tries to leave the courtroom after the trial. The audience never sees Shylock again. He is excluded from the happiness and joy in Belmont’s final scene; he is left a shell of a man, alone to suffer in Venice.

When the playwright and poet, Ben Jonson, a contemporary of Shakespeare’s, wrote in his elegy that his friend was “not for an age, but for all time” (Jonson 42), I do not think he was referring to The Merchant of Venice, specifically. However, in light of recent events around the world and the ubiquitous increase of vandalism, bomb threats, intimidation and protests fuelled by Jewish hate, it seems this classic Elizabethan play resonates as much today in Toronto as it ever did elsewhere. These are indeed dark times for humanity. And as my community continues to mourn all the innocent people who have and continue to be victims of the atrocities on and following October 7, I can not help but hear the echoing of Shylock’s words as he tries to make sense of the cruelty he has faced from perpetrators, like Antonio, who do not share his religious beliefs. “What’s his reason?” Shylock asks rhetorically. He answers his own question: “I am a Jew” (3.1 54).

Works Cited:

Jonson, Ben. “To the Memory of my Beloved, the Author Mr. William Shakespeare”. Folio of Comedies, Histories & Tragedies. London: Jaggard and Blount, 1623

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Canada: HBJ, 1988

Shakespeare, William. The Tragedy of Hamlet. Canada: HBJ, 1988

6 Comments

This is indeed a sad time in our world for us all but especially for young people as they look not only to their future but also

what life is like right now for so many people in war zones that continue to take the lives of each other and the opinions on

all sides regarding those most involved in these wars and of course the former history in the world of antisemitism that has

always been hard for me to understand. My best friend in high school was Jewish and her family and familys of Jews I have

met have always been people who use their lives and talents to quietly support all their friends and fellow citizens.

Hi Jodi , loved your essay on The Merchant of Venice and it’s meaning and connection to the antisemitism of today and Oct 7th

Your students are lucky to have you as their teacher and all of us appreciate your insight and thoughtful comments about antisemitism and it’s long historical presence.

fondly

Sheila Baslaw

Thank you for this timely post. The discussion of Shylock and Shakespeare brought to mind a book I read long ago. Libi Astaire’s “The Banished Heart” is a subject matter that takes another look at the complex mind of the Bard. This fiction resonates with today’s dark times. Back in 2015, my review of the book stated, “I was right there- in the moment- with Paul Hoffmann as his heart breaks while the world turns ugly and cruel, with Henry Rivers as he seeks justice, with Old Isaac as he shares his wisdom and love of tradition, and of course, with Astaire’s conflicted and shattered Shakespeare.” Astaire’s novel is thought-provoking and stirring, as is Nathanson’s piece. After October 7th, Shylock’s “I am not well” speaks to all of klal Israel. However, we have survived hatred and bigotry for over five thousand years. We will survive and thrive again. Am Israel Chai.

Thank you for this incisive and harrowing commentary. The Bard does continue to catch us in all our complexity, and I doubt if he would be surprised by any of the horrors which are happening today. Your students are lucky to have you to help them learn how literature can change our perspectives and our lives.

Jodi, this is such a wonderful article. Thank you for sharing!

A truly excellent article. This has always been a complicated play to read , to watch , and to teach. Mrs. Nathanson articulates with poignancy its continued relevance. Shylock’s final reflection is indeed “art imitating life” without the boundaries of place and time.