Even though his name is spoken often in my family of origin, none of us has ever met Ezekiel Coloneo. He died in 1753 – a date so furrowed into history as to seem impossible. And yet he stands there, proud at the top of our family tree (a grid of lines and names on thin squared paper in my grandmother Rosa’s nervy script) – a far-off patriarch, the furthest back we can trace.

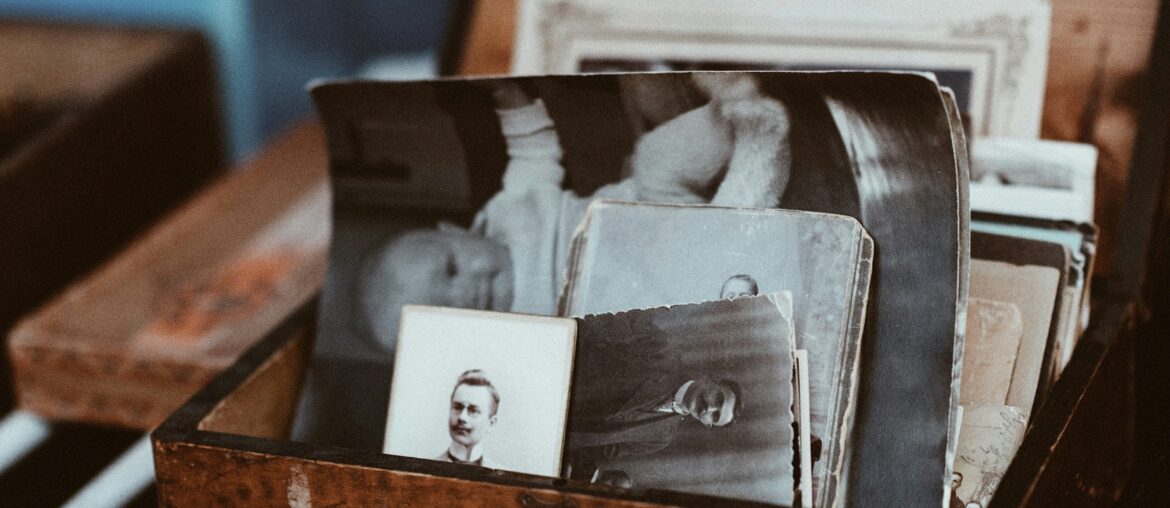

Rosa didn’t share with us her forays into genealogy before she died; we found her notes and microfiche photocopies years after she passed, so there is no way now of knowing how she set about it, how she tracked our ancestors down through the centuries to this one man – a name more grandiose than the Michaels and Ruths and Esthers who came after him.

I remember sitting one night with my Aunt Sarah in a New Cross pub after she found Rosa’s papers. We spread the papers out across the table, propped among the sweating glasses. Uncle Joseph joined us at some point in the evening, followed by his daughter Lou and several other cousins. I sometimes felt awkward among them, as I’d been raised by other people and didn’t share their shibboleths. But they’d welcomed me back, when I found them.

That night we pored over Rosa’s handiwork. Some of the names she had annotated with side comments. Some had codes that led to stapled newspaper cuttings or photos the colour of barely-brewed tea. Common East London lives – a suicide; a pub lost to a gambling debt. But it was Ezekiel Coloneo who stood out. Just his name was enough to fascinate us. Ezekiel Coloneo. The rhythm of an operatic aria. The tread of velvet shoes on polished wood. Enough to weave a hundred stories to explain him. A Covent Garden dandy. The son of a merchant shipman. A vaudeville chorus boy, or a Spanish rabbi’s right-hand man.

Over the years he became our way of explaining ourselves, of excusing certain facets of our personalities. He also helped us talk to one other when we couldn’t speak the words we meant to say. I’m sorry we didn’t see you grow up. We tried to keep you. From time to time, he even acted as a stand-in for the members of the family who’d disappeared. My father, for one. Absent since before my birth, he’d left a tattered hole in our communal fabric. But through our invocations of Ezekiel we brought him back. Through conjuring a series of different lives and different possibilities, we convinced ourselves that my father was well, and happy, and loved, wherever he was.

When we found out he was, in fact, dead we didn’t talk about Ezekiel for many years. We didn’t need to anymore. Somehow it felt like mentioning him made a mockery of what had happened. There was nothing romantic or heroic in the way my father died: bronchitis gone bad, alone in a Birmingham homeless hostel, found by the staff.

Now, when I see my aunts and cousins, which isn’t so frequent anymore (life threw us off in separate directions), one of us will bring up Rosa’s family tree. We’ll speak of names that we remember, stories that have stuck, and every time it comes back to Ezekiel. I suppose it always will. It’s easier that way.