While walking in Paris, I had a habit of looking up above the street level door to read the many commemorative plaques. In Montmartre, the historic creative and bohemian epicenter in the 18th arrondissement, these plaques were affixed on so many buildings. Now it is mostly full of tourists and street vendors, no Toulouse Lautrec or Satie in sight.

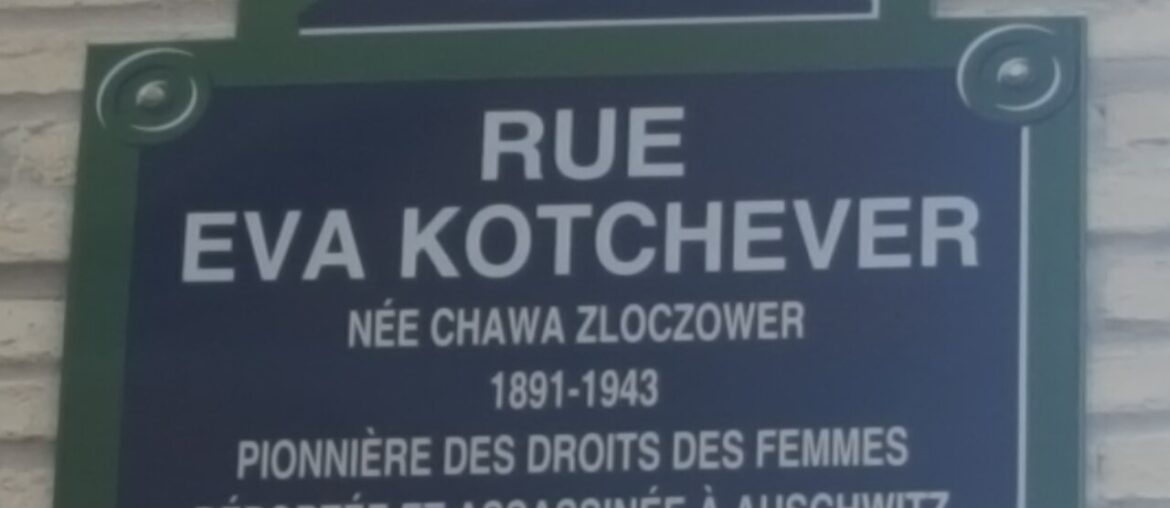

I must have taken a wrong turn as I was headed to the Porte de la Chapelle Metro stop. Instead I found myself at Rue Eva Kotchever, a rather dull little street of concrete and mini-trees shoved in pots. Translating the plaque, I learned she was born as Chawa Zloczower in 1891, became a pioneer of the rights of women, and deported and murdered at Auschwitz in 1943.

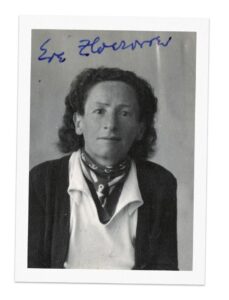

I had never heard of her, but clearly, she was someone who deserved some investigation. I discovered she led an audacious, pioneering life. For the rest of this essay, given her many morphs of name, I will refer to her as Eva and use the Anglicized spelling of her last name (Kotchever).

The oldest of seven children, Eva was raised in an educated Jewish family in Poland. Eva learned and spoke seven languages. At age twenty in 1912, she immigrated to America, calling herself ‘Eve Adams’. There she could come out and wear what she wanted, rather than what was assigned to her gender. At first, she traveled around selling anarchist publications, befriending a famous Jewish radical, Emma Goldman, whose poetic words are inscribed on the Statue of Liberty. ‘Give me your tired, your poor…’. That’s what America was in those days for millions of threadbare and persecuted immigrants. Eva’s politics and friends put her on the police’s agitator list.

During 1921, Eva settled in Chicago with her lover, a Swedish painter named Ruth Norlander. For about eight months, they ran a tearoom and literary salon named ‘The Gray Cottage.’ Her openly gay life attracted customers who wanted the same for themselves.

Fast forward to 1925. Eva returned to New York City and opened a night spot in the basement of 129 MacDougal Street in bohemian Greenwich Village. This was the first ever literary salon and social space catering to gay women. However, it welcomed all genders and sexual orientations. It was called ‘Eve’s Hangout’ or ‘Eve Addams’ Tearoom.’

That same year, she wrote ‘Lesbian Love,’ a collection of short stories about the lives of lesbian women, under the alias ‘Evelyn Adams.’ This book was likely the first detailed, honest ethnography of lesbians in America. Only 150 copies were circulated privately (one copy has survived).

A year later, an undercover vice squad officer who falsely claimed that Eva made advances to her caused Eva’s arrest for obscenity (her book) and disorderly conduct. Eve’s Hangout was shut down, and she spent a year and a half in jail. Upon release in 1927, she was deported to Poland where she bummed around various Polish cities. Her letters to friends described her difficulties with both low wages and antisemitism.

In 1930, Eva moved to Paris, where she worked selling books on the street, mainly to American tourists. Her life was centered around Montparnasse café society of sexually liberated writers and artists. Three years later, Eva began a relationship with Jewish singer Hella Olstein Soldner and lived with her even after Hella married. They intended to emigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine and join Eva’s brother but sadly lacked the financial means to do so. It would have saved their lives. In 1940, the Nazi takeover of France with its collaborationist Vichy government caused Eva and Hella to flee Paris for Nice in the south. So many Jews and others on the Nazi hit list sought any avenue of escape.

Many French policemen willingly looked for Jews to round up for the Nazis. So it was in 1943, the pair were arrested by the local police, imprisoned in an internment camp near Paris, and deported by a cattle car train to Auschwitz. They died in the gas chamber two days later.

Eva lived in a time when it was culturally and legally dangerous to be openly gay. Her commemorative street in Paris was part of honoring her legacy. However, the words on the plaque skirted the truth and left out a ton.

Thankfully, Eva Kotchever is now remembered as a Jewish lesbian who built a community and offered sanctuary to those who, like her, wanted a place to be themselves.

1 Comment

Dear Emily;

Thank you for bringing Eva alive in your writing.

I love reading short stories about people who are often forgotten.

Sharon Easton; Storyteller, Writer

Beach Moose & Amber: Finding My Jewish History

Writer’s Union of Canada, Canadian Writers Association, The Federation of BC Writers, and Around Town Tellers Nanaimo

Website: https://www.sharoneaston.com

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/sharoneastonauthor