No one noticed that I was gone.

On the hot August day, the funeral over and the onset of the Jewish ritual of sitting shiva, I went upstairs to escape the crowd of people downstairs. I pulled my sweater closer to my body trying to keep warm. Shaking, unable to know whether to stand or sit, I leaned against the edge of a hard yellow leather chair looking out the window. The stillness of the trees, multiple cars lined our street and the adjacent side streets. Muffled voices carried throughout. The door opened and closed with a loud thud. A ring of the doorbell startled me. A no no in a shiva house. The coffee aroma drifted upstairs made me nauseous. My heart ached, tears streamed down my cheeks, my nose ran with no Kleenex around. Margie gone, Jane gone, I’m alone.

Thirty-one years ago, my sister Margie died at age thirty-five. Eight years earlier my only other sibling Jane died at age twenty-two. For thirty years I suppressed my grief. I took on the role of caretaker for my family. My grief took a back seat.

My family did not talk about my sisters due to their immense grief. Haunted I would forget Margie and Jane.

Grief is not a topic people are comfortable talking about, nor sometimes can individuals going through grief comprehend what they need.

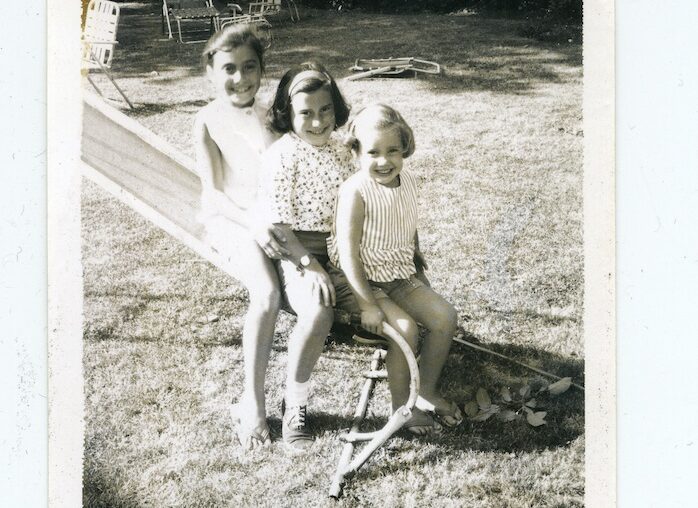

I needed help and was fortunate to get the necessary therapy. Reliving my sisters’ deaths buried so deep in my subconscious was daunting. Memories buried deep bubbled to the surface. Although the process was incredibly challenging, lost memories came alive – some dark but many filled with light. Old black and white photographs depicting three sisters dressed up in party dresses, white laced ankle socks, and black patent leather Mary Janes feeding the ducks in The Boston Common out for a special Sunday dinner at Stella’s restaurant in The North End.

It is never too late to grieve.

Thirty years was half my life. When I looked back at the landscape of my life, I recognised that those thirty years could be thought of as lost time. And I reminded myself how grateful I was to be undertaking this hard grief work. But my heart would not allow me the freedom of forgiveness. My brain needed an alternative pathway to peace.

Sibling death is referred to as a disenfranchised loss. Disenfranchised grief is a term coined by one of the esteemed grief researchers, Dr. Kenneth J. Doka twenty years ago. He defines disenfranchised grief as, “grief that people experience when they incur a loss that is not or cannot be openly acknowledged, socially sanctioned or publicly mourned.”

Often siblings are the forgotten mourners, overlooked and take on the burden, worry and caring of other family members. Siblings share a unique bond no matter the complexity of the relationship. They know you better than anyone else and whom you dream of sharing your life with. In an instant that changes. Navigating your life without your sibling(s) is a complex journey.

To be honest, there is little information about the numbers of individuals who have lost siblings. One study shows that 8% of people up to age 25 have lost a sibling. The CBEM reports states that in the United States 1 in 14 children by age eighteen will experience the loss of a parent or a sibling. Some siblings channel the grief by choosing a way to honour their lost sibling(s). From erecting a memorable plaque, planning a walk, or running in memory of their loved one, creating a religious service on the anniversary date, writing poems, essays, and books. I chose to honour my sisters with an annual ice-skating fundraiser: Celebration of Sisters, bringing me full circle to a sport we all shared as girls.

But healing has taken place, through forgiveness and in acknowledging regret. After my sisters died, I never spoke of it. When asked, how many siblings do you have, I would answer, “just me.” Now when I meet someone new, I say, “I am the middle of three. Sadly, I lost both of my sisters.”

The resources for sibling loss include: The Open to Hope Foundation, The Compassionate Friends, and The Grief Toolbox.