When I shelved my law career to become a writer, the most common advice I was given was write what you know. I’ve always preferred write what you want to know. Write about the things that horrify and fascinate you. Write about the things that anger you, or that you struggle to understand.

I write to make sense of the things that scare me: war, misogyny, intolerance and violence, but mostly, hate. My father was a Holocaust survivor, so it makes sense that all my novels would take as their main protagonist a teenager fighting to live a life of their own choosing. It makes sense that what fuels my writing is fear.

I only came to learn my father’s Holocaust story later in life, when I was in my thirties and he’d been diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease, and given 6 months to live. My father had disconnected from the past as a way of moving forward. He’d kept his story from us, and his camp number hidden under a tattoo of a flower, because in Australia he didn’t feel like a number anymore, he wasn’t a victim. He was a boy remade into a man with a wife and three children, a home and community.

And maybe he never mentioned the camps because he didn’t want that chapter of his life to be our personal inheritance. Maybe he thought he’d one-up Hitler if, instead of passing on his personal trauma, he gifted us resilience, hopefulness, compassion and pride.

When he finally shared his history, I quit my job as a lawyer to write it down and shape it into story that would sit on shelves. I’d promised my father I’d tell the world what had been done to him and I kept that promise when The Tattooed Flower was published in 2006, but something kept drawing me back to the past. Fear.

What happened to my father when he was a kid scared me, and it made me angry. The fact that nothing had changed in the two decades since I’d written The Tattooed Flower, and that we were still hurting each other scared me too. What do you do with all that fear and anger? Revenge is nice but change is better. And who better to target than teenagers, who are still working out who they are, and what sort of world they want to live in.

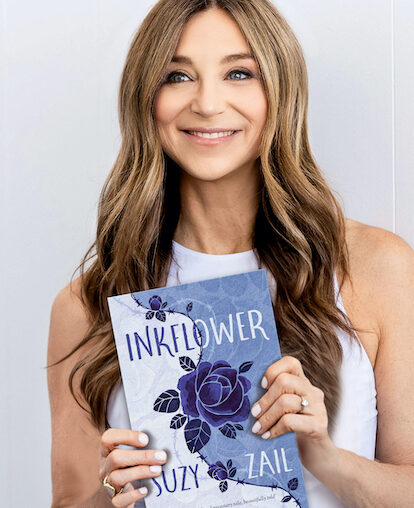

So, I set about writing Inkflower, a novel for teens. I had a good story – my father’s – a Holocaust history that was inspiring, despite its trauma; a history of resilience, rebuilding, resistance and strength. All I had to do was re-imagine it for a Young Adult readership.

The first rule of writing for Young Adults is: no adults as the main characters. Teenage readers want someone their age who they can relate to. Swapping myself out of the story with sixteen-year-old Lisa Keller, freed me to dig deeper, to create someone angrier and more unsure of herself than I was. Someone with more angst about hearing her father’s story, and more conflicted about her father’s disability and sharing it with friends. The beauty about fiction is you can direct the action. I could have Lisa anger, fail, struggle, learn, grow, have setbacks and grow again throughout the novel. I could have her do the things I wish I’d been brave enough to do, like wash and feed my father. I’d been scared, so I’d avoided it. Lisa was scared of her father’s frailty too, but I made her push through that fear. She’s me, but she’s braver.

The thing about writing a 16-year-old, is there’s nowhere to hide. You have to feel all the feels if you want to write an authentic character because teenagers feel everything and it’s all momentous and unbearable. My father died eighteen years before I started writing, and I don’t think, in all that time, I’d ever really broken down. My dad had raised us to build walls and let go of sadness, just like he had after the war. We Brauns weren’t raised to excavate our feelings, we dealt with them on our own, and moved on. We looked forward, not back. We were glass-half-full people. So, that’s what I did after he died. I thought of him, free of his disease and at peace, and I smiled.

When I’d sat down to write The Tattooed Flower, I never really stopped to let myself feel. It wasn’t until writing Inkflower two years ago, that I really grieved. I remember sitting at my desk, and asking myself How would it feel at sixteen to find out your father was dying? And How would it feel to be a fourteen-year-old boy torn from his parents at the gates of Auschwitz? How would it feel to be hungry, scared and alone? I sat there asking myself over and over . . . How would it feel? And I just started bawling. I let myself come undone.

Inkflower was a hard book to write, but there was so much that made me smile: Spending another two years with my father. Meeting the uncle and grandparents I’d lost to Hitler. My father had only every talked about them fleetingly, but after two years spending time with them on the page, I felt like I knew them. I felt like we were friends. Finding a black-and-white photo of my father at thirteen, the only photo we have of him from before the war. Discovering a testimony he’d given to the Holocaust Museum and seeing him on screen, talking and smiling and wiping away tears. Receiving a sprawling family tree linking me to 122 uncles, aunts and cousins. But mostly, giving my father back his voice. He’d had it stolen twice, once by the Nazis and then by Motor Neurone Disease. Writing Inkflower was a way to help him reclaim it.

The book also let me share the lessons my father had taught me in his last years, lessons like: Sharing your fears, shrinks them and; Celebrate today. And that small acts of kindness can be hugely powerful.

My father taught me that we have to talk about the things that scare us before we can change them. And so, I’ll keep writing about the things that scare me, in the hope that one day I can transform them into something beautiful and healing. Words to help move us closer to a world in which we all feel safe.

I think my father would like that.

Inkflower is available online and in all good bookstores.