The news is on television. ‘Aren’t you glad your great-great-grandfather left the Ukraine?’ I said. My Australian sons agreed. My very Australian grandsons looked at me for explanation. So, I told the story – again.

My grandfather Nathan and I met only a few times and since he never learned much English and I could not speak Yiddish or Russian, communication was very limited. He lived out his life in Cardiff, Wales, and when he visited us in London, I was very young – ‘a sheyn meydl’ – a ‘pretty little girl’ – he told my mother, his eldest daughter.

My cousin who knew him well told me the rest. Nathan was from a poor family in Ignatovka, twenty-one kilometres east of Kiev, and like many young Jewish boys was conscripted into the Russian army when he was about twelve years’ old. I believe twenty-five years was the compulsory term of service. ‘Zaida’ – grandfather – went with the army to fight the Turks. ‘We ate sandviches filled with vorms’, he said.

In c1892, by which time he was 28, he was eligible for a leave pass. It allowed him to travel ‘in those places of the Russian Empire where Jews are allowed to live’, namely the area known as the Pale of Settlement. It was a three-month pass with serious consequences if Nathan did not report back to the barracks on time. He never returned. He left Ukraine for London arriving at the docks with his worldly goods wrapped in a cloth like Dick Whittington and just a piece of paper with the address of a ’landsman’, someone who had also come from Ignatovka.

In 1923 representatives of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee visited Ignatovka and wrote a report. In 1919, General Denikin’s troops had led a pogrom and wiped out most of the remaining Jewish community. The report ends with the observation, ‘Ignatovka no more resembles a town.’

Nathan never again saw his family in the Ukraine, but my cousin remembers that his sister sent letters. In Yiddish? In Russian? The letters ceased abruptly in 1941. Seventeen kilometres from Ignatovka is the site of the ravine called Babi Yar. In two days, 29-30 September 1941, 34,000 Jews from Kiev were murdered here. Stripped naked, shot in the head, and flung into the huge trench.

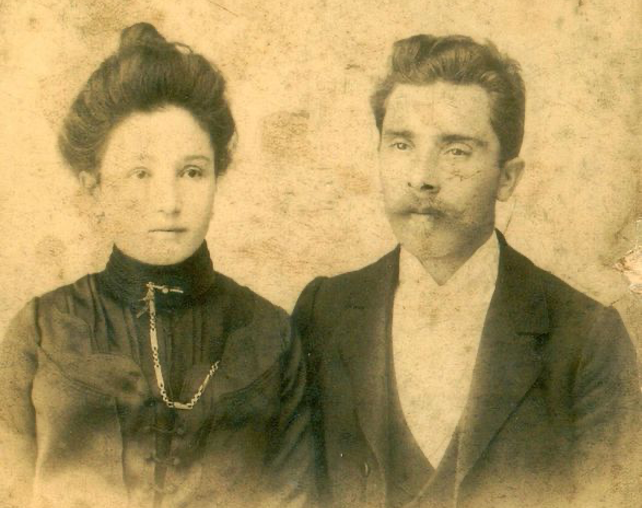

Today, here in Melbourne, Australia, as I read about the Ukraine, I feel immensely grateful that Nathan had the courage to leave. I look at a few faded photographs: Nathan, my grandfather; and the saddest of pictures – his unnamed sister, the letter-writer, and her husband – who I feel sure must have perished at Babi Yar.