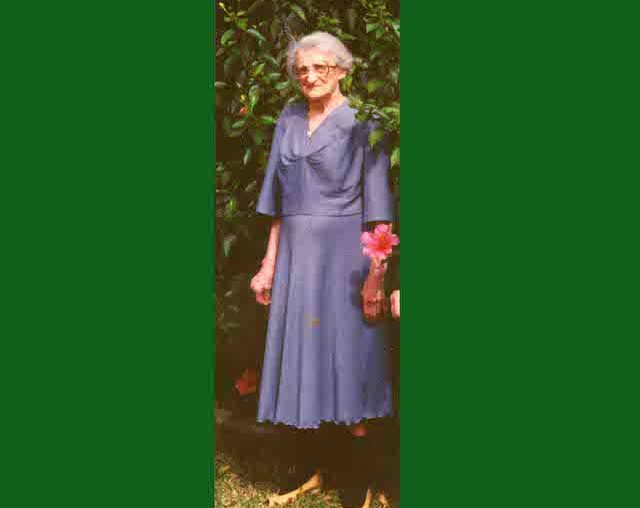

Her feet were old. It was the first thing I noticed about them. If it were the 1950’s, her shoes would still be out of fashion. Yet, mama pulled these worn shoes from their original box with care and jubilant pride. It was the end of the twentieth century and she was certain her shoes were more beautiful and stylish than any American woman could hope to emulate.

“Uncle Sasha gave them to her,” her son explained. “He picked them up in Romania on a business trip because he loved his great-niece and missed her. She cherishes them. They are probably thirty years old. In our time you could only afford straw shoes in Moldova. These are precious to her. She wore them from Bendery all the way to America when we were refugees.”

Her son explained this to me in case I might say something arrogant, like Come on mama let’s go buy some decent shoes.

The old shoes were well worn and had a fake, yellowish leather look, with stubby heels. Mama teetered when she walked into shul each Shabbat. I feared she’d fall over, but she never did. All the former Soviet Union ladies wore shoes like hers. Each one wobbled, but no one turned their ankle. No one fell. I’d admire them as they pranced to their seats, adjusting their hand knitted hats, wearing dark dresses they’d made when they were young mothers. Now, they were in their eighties and each had a wooden cane that resembled their grandmothers’ canes two generations prior.

They’d left their pictures and memories in Moldova, packed two suitcases and vanished from the homes their families had lived in for five generations. They wore their coveted, dress-shoes as they left Russia; they took one additional dress besides the one they chose to wear on the road to freedom. A few took a pair of snap on ear-rings or a necklace they’d been given somewhere along the line. They grabbed onto the hands of their adult children, grand-children and would not let go.

But they’re gone now. Their lives have ended. Mama was born before the Russian Revolution. She witnessed many forms of genocide in her days. She’d managed to fasten the loss she’d experienced at the hands of violent politicians onto the air that surrounded and comforted her once she made it to America. She imagined how the actions of these malevolent criminals could be imagined into strong breezes giving her the power to simply watch sadness and loss disappear into clear blue skies. Even dead loved-ones became mere pixels in her fading memory.

“Let God remember wars and look into the eyes of our dead. My pockets are full with memories of children, gardens and the Black Sea. It’s better to let God deal with evil-men and the footprints they wish to impale upon our faces. I have discovered where freedom lives.” It did not take long for Mama to believe in America.

It is now 2022. We’ve become Americans. Mama would be 108 years old today. Before she passed away, she became an American too, but the shadows of Moldova, her beloved country, never left her smile. When she laughed, when we watched her joyfully pick out her best clothes and aged shoes, we’d remember where we came from. Instead of gardens, children and the Black Sea tucked deeply inside our pockets, we were taught to carry mama’s stories and experiences. Truthfully, as the decades continue to pile up and we become the elders, mama’s memories are all we own. They are all we need to be responsible for.

Of course, it was bound to happen—another episode of slaughter fizzing its way into the world like a bomb blasting vintage champagne that failed to keep its promise of sweetness. For us, there was no escaping real time. One thing you can say about the 21st century is there is no buffer, no time delay; no black and white photos or film portraying after-thoughts from those who sit in their living rooms, crowing like supercilious flocks of chickens. These voices are never silent:

“No. That did not happen.”

“You whiners!”

“No one murdered you—you just died.”

“It was not that bad.”

“If you were hated, it was because you are a worthless people and deserve to be eliminated.”

Moldova is in the cross-hairs once again. This time mother-Russia came back, threatening to open our graves, rewrite our history and replace it with her private sense of belonging and expansion. After all, corpses rising from tombs like restless glamim have plagued our enemy’s dreams since time began. Atrocious images build up. In fact, they fester, swell and then explode.

No one is completely evil; they merely want God out of the way. They can do a better job turning blood to dust and rebuilding in their own image, their own rules. It’s the pursuit of idolatry. Our enemies chose to worship their own shadows while enjoying Odessa on a pleasant summer day. It’s as simple as that. They consumed the wine of Moldova and called it their own. Perhaps after murdering us and destroying our towns they looked forward to lunch on the veranda while planning a trip to Crimea. The beaches are pristine there. It’s a good place to rest. Of course, they’d forgotten to figure in the Black Sea maintains its deep dark, oily soul because of the decaying bones of our missing elders and children.

I am trying to make sense of World War III looming above the horizon, about to replace the sun with its own source of heat. Will our history become our future?

I think.

I pray.

I think I hear G-d crying, or is that G-d screaming?

I refuse to answer the telephone.

I refuse to wipe away a tear.

I create a package addressing it to someone named Dis-belief.

I argue with silence.

I reach into enemy pockets and extract pictures of our dead.

I retrieve mama’s stories from hidden places. Surprisingly they’re in colour.

I remember mama’s stories are her precious smiles.

I begin to write poetry that has an unfamiliar melody.

And then, you see it— a flat screen smart-TV has taken over the air we breathe and the space we’ve come to believe in. That’s our melody. A narrow trench that might be a mile in length becomes the only horizon we’ll ever be able to remember. It’s deep and the soil that makes up its depth appears fertile and black with snow geometrically piled on each side. It all looks so inviting as if we’re looking at a never-ending chocolate birthday cake topped with frozen whipped cream. The sadness? No one has the courage to light the candles or wrap themselves in song. Perhaps it has nothing to do with courage and the lack of illumination is because there’s no one left to strike a match?

We cannot close our eyes fast enough. We’re overcome with loneliness: crisp, clear images of elders, babies, children; slick black bags, bodies wrapped inside colourful blankets meant to keep a grandmother warm and secure pour into our eyes. We’ll never cry again. They all disappear into an ocean of stiffening color. Bare legs protrude into the air as if searching for an escape; an occasional hand tries to wave good-bye. The dead are still wearing their best shoes- the shoes they prayed in, the shoes they smiled from. The shoes are now seeds, but no one believes anything will bloom once spring finally wakes up. No one believes in colourful, beautiful gardens any more.

Suddenly, it’s the end—family members, neighbours, the mayor, soldiers who did not have time to put on their uniforms grab shovels and long blades and the mile long trench becomes a mass grave covering what soon will become nothing. The last shot, the last image broadcast onto our American television are a pair of lady’s shoes, yellowish, stuffed with earth that resembles the vineyards of Moldova. Miraculously, I was sure they were Mama’s old shoes, the ones she cherished, a gift from her elderly uncle because he missed her smile while joyfully travelling beyond the homeland.