I had very little interest in history growing up, at least not the kind they taught in school. I loved the history I got from the books I was secretly reading off my mother’s bookshelf: The Iliad and Odyssey, War and Peace, Things Fall Apart. Turn the dates and deeds into a story that involved people I cared about (which generally weren’t those who wielded big weapons on the battlefield or sceptres on a throne) and I was hooked. If you could make a piece of theatre out of it that involved a love story and a few songs (Cabaret, Evita, Fiddler on the Roof) so much the better and I would happily dance around the room at a ridiculously early age, singing about antisemitism, tradition or Argentinian politics.

Every history, whatever the form, is a new story, a unique creation, pieced together from incomplete data, fragments, scraps, and the bias and judgement of whoever is creating the history at the point of that creation. History is in the eyes of the beholder and the meanings and perspective will always be a unique combination of material and storytelling that will, of necessity, be subjective and selective. Of course you can string together a set of dates confirmed by reputable sources, but these really don’t make up a history as such. For that you need to add imagination and maybe something else – a kind of personal engagement. Otherwise it’s little more than another artefact for someone else to create with: material.

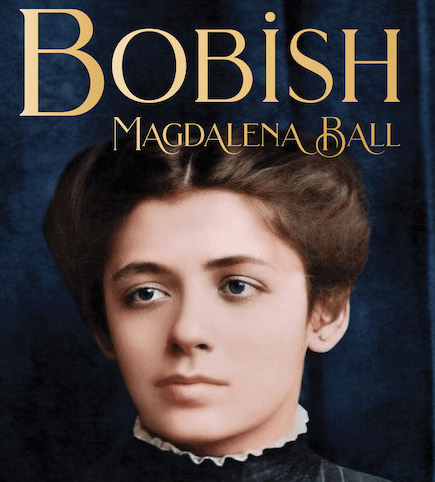

When I was working on my great-grandmother Rebecca Lieberman’s story, the work that would eventually become my poetic memoir Bobish, I was limited by the material I was able to access. Rebecca died before I was born, and there were only two family members alive who knew her and they only remembered a very little bit – fragments really. I asked them a lot of questions, probing for any memories I could stimulate. I also read a lot of books about the pogroms, about the Pale of Settlement which Rebecca left at the age of fourteen to sail on her own to New York. I was able to access census documents, records, a few memories my mother passed on along with the photo that graces the cover, and my aunt Susan’s memoirs, Take the Long Way Home (Gordon Lydon, HarperCollins, 1993), which opens at Rebecca’s house where Susan lived with my grandmother Eve while my grandfather was away during WW2. Both Susan and my mother knew Rebecca and Simon, her husband (my “fish smoker”), but all of these were fragments.

I spent hours on Ancestry looking for more, but the city Rebecca grew up in is no longer really there. Most of the village was destroyed and records burnt. Any of her family that were left behind who weren’t killed by the pogroms or during the first world war would have been killed during the second world war as all of the Jews in her village were reportedly rounded up, brought into the forest and shot by the Nazis. So I couldn’t go there and speak to people, or rifle through old records in a library as these things do not exist anymore. Much of what happened would not have been recorded anyway, but if anything had been written down, it would have disappeared as surely as the bones of all of Rebecca’s ancestors.

Sadly, this is not an unusual story. I hear from many people that this is also their family’s story. It’s a story I couldn’t let go of. The relationship between the grand sweep of historical events and the intimate details of my unknown great-grandmother had gotten under my skin. I was dreaming about her, and my research continued. I contacted historical societies to try to get some help. I began learning Yiddish to get a bit closer to some innate part of her identity and my own as well. Rebecca’s daughter, my grandmother Eve, didn’t speak often of her mother, but I knew a few things. I knew that she sang the same lullabies in Yiddish that Eve sang to me – Shlof, mayn kind. I knew that that Rebecca worked in the ill-fated Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and that she didn’t go to work on the day of the fire. I knew that husband Simon, my great-grandfather, was an alcoholic and abusive. I knew that Rebecca read tea-leaves and claimed to be able to see the future. I knew that she died early from complications of diabetes and was nearly blind at the time of her death. I don’t know exactly how I knew these things – they are part of the family mythologies I grew up with.

Rebecca wasn’t a hero. She didn’t do anything that you’d normally write about in history books but there was something in her story about trauma, migration, hereditary, survival and healing that felt important. I first tried writing a novel but it didn’t work. The tone was too certain, the story too linear, and the need to create a novelistic scaffold for what was a complex and messy story was too far from what I felt to be the truth. I wanted to lean into the uncertainty. I wanted to allow the impossibility to be part of the story. I wanted magic, and tea leaves, and love, and above all, I wanted to make this as much my story as hers, I wanted to compress and expand time and distort it in all sorts of nonlinear ways, and to do that, I needed the subtlety of poetry. I could explore what I didn’t know by being open about it, and by playing with that impossibility. The not-knowing opened a space where I felt it was possible to intuit my way in. I knew my grandmother and I knew and felt all of the pain of her mother in her beautiful Yiddish lullabies that made up my childhood. Of course I never went through the direct trauma of Rebecca’s pogroms, or the knowledge that my immediate family had been killed while I survived. But it is precisely my safety now that allowed me to go to where Rebecca was hurt and create a story of both pain but also of healing, working backwards from where I am to where she was through my mother and grandmother – a whole line of DNA that felt as familiar to me as my own skin. I may well be wrong on many counts, but given the many accounts I found in other people’s stories along with the specific artefacts of Rebecca’s, I knew that there was enough of a parallel to the many similar stories for this one to be close enough. Piecing together the artefacts – the letters, stories, books, images, postcards, bits of fabric, audio recordings of street sounds and official documents into something that is coherent and engaging is a a creative and impossible act, but it is, in many ways, as much truth as any historical account can be.

Magdalena Ball will be at the Sydney Jewish Writers Festival on Sunday 27 August. Magdalena joins yoga instructor Idit Hefer Tamir to find new avenues of self-discovery in a remarkable session ‘Morning Yoga – Poetry & the Body’ and moderating the session ‘Women on the Verge’ with authors Katia Ariel, Elise Esther Hearst and Kerri Sackville. Shalom’s Sydney Jewish Writers Festival runs from 23 – 27 August 2023 at the Bondi Pavilion. Exploring the theme of ‘Identity’, the Sydney Jewish Writers Festival program has three streams of exceptional writers, poets, musicians, playwrights, comedians, and thinkers who promise to explore the theme of identity from every angle. Booking Link: https://www.shalom.edu.au/event/sjwf-2023

2 Comments

My maiden name is Bobish. My great great great grandfather came over thru Ellis island from Slovakia. The original surname was Bobos then changed to Bobish. Where does the name come from? Was it the man she married? What was his name? We could be family!

Abby (Bobish) Smith

Pingback: Jewish Women of Words | Magdalena Ball