Rebecca Forgasz was the Director & CEO of the Jewish Museum of Australia for nearly ten years. This extract of her farewell lecture, Ten tantalising tales: stories from our collection, is part of a series published here to mark the High Holidays. In each instalment Rebecca reflects on the personal, collective and cultural significance of objects and the collections that house them.

#3 Marriage certificate

The story of the Marranos—secret Jews of Spain—is relatively well known. But far less known is a similar story of Jews who lived in Persia in the 19th century. That is the story told by this Islamic marriage certificate, which belonged to the grandparents of the late Ben Elisha, a GP and artist who lived in Melbourne.

Jewish life in Iran can be traced back to the deportation of the Israelites in 724 BCE from northern kingdom of Israel to the cities of Medea and Persia, and of course, the story of Purim is set in Persia around the 4th C BCE.

The period of time relevant for this object is 18th C in an Iranian city called Mashhad. In 1735, a new ruler Nader Shah, invited some 40 Jewish merchant families to come to live in Mashhad, a holy Muslim city where previously Jews had been forbidden entry. He believed that their business acumen and international connections would spark economic prosperity for the whole region.

So, the Jewish merchants and traders came, and prosperity did indeed follow for both Muslims and Jews; within a short time both Jews and Muslims in Mashhad began living lives of wealth and privilege. Nevertheless, many local Muslims continued to regard the Jews as unclean and refused to accept them socially.

In 1747, only 12 years after Nader Shah first invited the Jews to Mashhad, he was assassinated, and Jews once again became second-class citizens. Once again, they were refused entry to parts of the city and forced to wear identifying marks on their clothing. Their status continued to decline over the coming decades.

The day before Pesach in 1839, a blood libel led to a devastating pogrom. Muslims attacked the Jewish community, burned synagogues and destroyed Torah scrolls. Thirty-six Jews were killed and many wounded. Around three hundred Jewish families were forced to take Muslim names and convert to Islam.

From all appearances, the Jews of Mashhad had truly converted: they began attending services at the mosque, appeared to fast during Ramadan, wore Muslim garb, and bought halal meat and Muslim-made bread. But at home, in basements, behind closed doors and shuttered windows, they secretly continued to observe Jewish law. This continued right through to the 20th century.

In a 2007 article in the Jerusalem Post, Rachel Betsalely, who left Iran for Israel with her family in the 1960s, recalled how they lived their double lives. “They were very clever,” she said. “Outside the home, they were Muslims. They shopped in Muslim stores and observed Muslim holidays. But at home, they were Jews. They had many little ways of maintaining their Jewishness—Shabbat candles were always lit under cover, so they couldn’t be seen from the windows. Families kept dogs and cats, so they could feed them the Muslim meat they bought while they themselves ate kosher meat, shechted [ritually slaughtered] in secret and smuggled home under the women’s chadors, or long cloaks. In the market, the Mashhadi purchased Muslim bread like everyone else, but as they walked home, they gave the bread to the Muslim poor. In their basements they ground their own wheat and baked their own bread.”

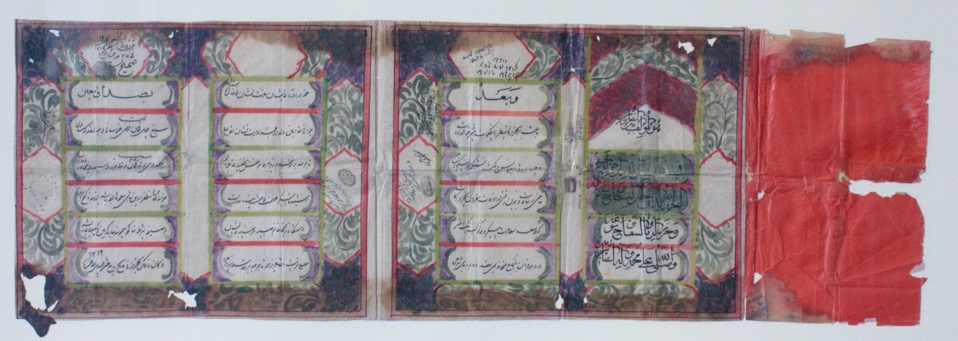

This document is an Islamic marriage that belonged to Ben Elishah’s grandparents whose family had converted to Islam, but preserved their Jewishness in secret. They married in Mashhad in 1899 when the bride was 12 years of age. Early marriages were common and designed to prevent a difficult situation should a Muslim man ask for the bride’s hand in marriage.

Ben discovered this marriage certificate, and, as he was opening it, he found, tucked behind, this: a ketubah, or Jewish marriage certificate, from the Jewish wedding that had been carried out in absolute secret. Here, the couple’s Hebrew names are used: Benjamin son of Elisha and Miriam daughter of Azariah instead of Amin son of Ali and Zvlaikha daughter of Azizullah as they appear on the Islamic marriage certificate.

What a thrill to see this material evidence of the double lives led by these secret Jews, mirrored even in the way they were preserved and discovered.

Ketubah – Persian Wedding Certificate

1899, Meshed, Persia

Paper, ink, 760 x 535mm

Donated by Ben Elisha, in memory of the donor’s father, David Elisha

Jewish Museum of Australia Collection 10556

Comments are closed.