Professor H. Broaden wasn’t broad. Everything about him drooped.

His lips dropped, his shoulders drooped, his jacket drooped, and when he smiled, his eyelids drooped, like those of a lizard, smug and venomous.

And it was with that lizard’s smile that Professor Broaden sat down to Mrs Plotkin’s Passover table.

Mrs Plotkin raised the matza. “This is the poor bread…”

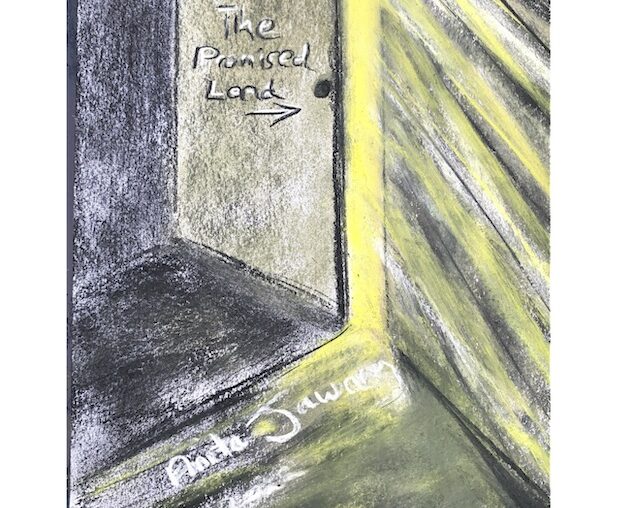

Her daughter, Clara Plotkin, gazed at the ceiling as though the promised land lay somewhere beyond the chandelier.

“We must drink four glasses of wine, Professor.” Mrs Plotkin ‘s cleavage quivered as she filled their glasses.

But for all her cleavage and matza raising, Professor Broaden paid her scant attention. He could not take his eyes off Clara.

Clara was watching the front door. As was the custom on Passover, the front door was open. It let in cold gusts that blew down the corridor and menaced their table.

But, open as it was, for Clara the door may as well have been locked.

She was unable to leave, and neither Elijah nor any stranger was going to pass through it. Not even her father would walk through that door.

With each gust of wind, she saw him there. The way he used to walk in, almost shy to kiss her. He would pat her head and smile, and put his briefcase down, and in that small, shy act, she was safe.

Now there was Professor Broaden.

“We give thanks, Professor,” explained her mother. “God brought us out of slavery to the Promised Land.”

“Do you really believe that, Mrs Plotkin?”

“Of course. You can call me Doris.” And with her smile she held him with her eyes a little too long for Clara’s liking.

“Clara, help me explain to the Professor.”

“You invited him. You do it” She scowled at her mother and went back to staring at the front door.

A brutal gust of air flew down the corridor and stung their cheeks.

Mrs. Plotkin soldiered on. “We celebrate Passover every year, Professor, because…”

“Well! you celebrate a myth,” he mocked. “A fairytale!” He beamed in triumph at the two women. “And if there really were a God, and if there really were a Promised Land, do you think this God would have given it to the Jews?”

He skolled his wine. A red droplet hovered on the droop of his overly moist, pink lower lip.

There was exaltation in Clara’s eyes as she watched her mother pallor. This man sitting here! Her father gone!…it was all her mother’s fault, and she deserves what she gets.

Mrs Plotkin looked from one to the other, like a wounded rabbit not understanding that the huntsman was about to shoot the final shot.

She had done the right thing. She had followed the injunction to welcome the stranger. Let all who are hungry, come and eat.

Mrs. Plotkin contemplated the open door. It has brought no promise of suitor or smile. Then she turned to Professor Broad. Her lips were trembling and she looked as though she were trying to articulate something, but no sound came from her lips.

A particularly ferocious gust of wind blew down the corridor and the candles on their table almost went out .

“That damned door!” cried the professor. And he ran to shut it.

“No!” Clara’s voice, sharp, like lightning.

The professor slowly turned. He contemplated the two women.

“Well…” and his eyelids drooped down over his eyeballs. “I think I’d better go.”

Clara stared at the empty corridor. Even though the doorway was empty, even though her father would never return, he was there, he was there, he was walking down the corridor, he was coming toward her, he would pat her head, shy, almost, of his own touch, he would put down his briefcase, and she would be safe once more.

Clara felt her mother’s hand, ever so gentle, envelope hers. And, this time, Clara did not flick off her mother’s touch.

The two women sat at the table, exposed to the wind of the open front door, and read, together, about the path, out of slavery, to the promised land.