Sometimes the world’s problems weigh so heavily, that your very soul feels tired. I felt this kind of tiredness over the last weeks of 2018, with the latest round of Israel-Gaza fighting, the news of a 26th woman murdered in an act of domestic violence, and the announcement of early elections. Addressing such systemic problems feels beyond reach.

And then, I remember Rosa Parks’ tired feet.

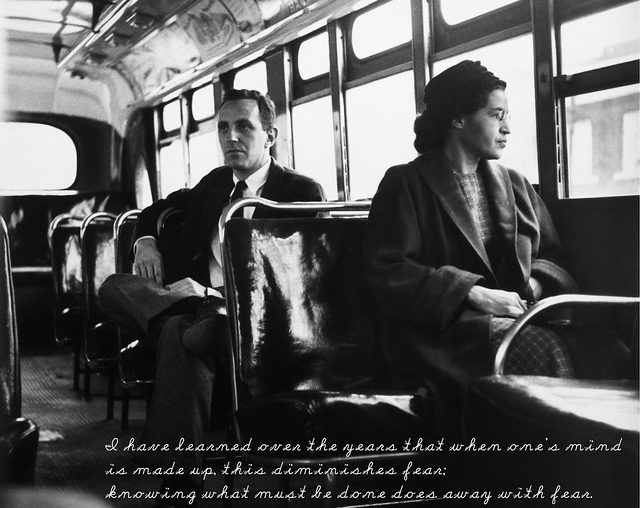

The story is told how Parks, a simple seamstress, was on the bus home after a long day’s work. She was tired — too tired to give up her seat to the white man who had stepped on to her crowded bus. This, however, was far more than a moment of physical tiredness. As Parks later explained: “People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was tired of giving in.”

The risks of resistance were great. Those who protested segregation faced harassment, being beaten, jailed or even killed; women feared the possibility of rape. While Parks was not alone in being long tired of the daily systemic segregation, she and a small number of activists were alone in their efforts to seek equal rights and decent treatment.

But on this day, her refusal to comply with the norms of the Jim Crow South led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which paved the way for the undoing of Southern segregation.

What made this incident different from all others?

The bus boycott began on December 1, 1954, four days after Parks’ refusal to give up her seat and subsequent jailing. Day in, day out, in the extremes of winter cold and summer heat, people walked miles to get where they needed to go. An elaborate system of car rides helped ease the burden, but the drivers and passengers were often harassed, and cars were vandalized or damaged by a range of vicious tactics. Many activists lost their jobs, and others received threatening phone calls at all hours of day and night. Some of these threats even turned into physical violence and bombings.

Yet, 385 days later, the courts ruled in favor of the protestors and buses were desegregated. The boycott had succeeded. This was a turning point that helped ensure the long-term success of the Civil Rights Movement.

It was neither lucky nor inevitable that Parks’ refusal to stand would transform the Civil Rights movement. In reading, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Jeanne Theoharis, I was struck by a number of insights about how to bring about systemic social change. These gleanings have much to offer those trying to address deeply complicated socio-political issues.

Core values

Rosa Parks found guidance and solace in deeply held values, rooted both in American ideals and religious faith. She knew that America should live up to its proclaimed democratic values: every person, regardless of race, must be treated equally, and with dignity.

“As far back as I can remember myself, I had been very much against being treated a certain way because of race, and for a reason that over which I had no control,” Parks said in a 1973 interview with Studs Terkel. “We had always been taught that this was America, land of the free and home of the brave, and we were free people, and I felt that it should be… in action rather than something that we hear and talk about.”

This values system helped her discern what was wrong with the dominant norms of segregation, and gave her the courage to act.

The practice of resistance

Segregation was both a way of life and a system maintaining hierarchy and fear. When Parks refused to give up her seat, it was not a simple spontaneous reaction. She was in fact already well-practiced in opposing the norms and demands of segregation. She had long refused to drink from “colored” water fountains, preferring to go without water if that was the only choice. She refused to use separate bathrooms. She refused to pay the bus fare, get off the bus and re-board in the back of the bus as was the norm.

Any single act might not have meant much in isolation, but collectively, Parks’ micro-dissents added up, resulting in a sustained practice of resistance that served her at this decision point.

Individual and collective action

For decades, few whites were interested in changing the status quo and few blacks felt they could. Parks was one of a small number of activists working against segregation years before the civil rights movement took off. “I felt very much alone,” Parks said about those long years of solitary activism working against the strong currents of the mainstream.

But Parks also found partners. She married a man who proudly withstood the norms of segregation in many ways as well, standing up for civil rights as early as the 1940s, and supporting his wife in her many years of activism. Parks also joined the NAACP at a young age, developing close working relationships with other activists.

With the boycott came the widespread support of the Montgomery black community, who united behind these efforts, and of people from around the country. These networks provided both the moral and collective support necessary to leverage these actions for wider effect.

Organizational infrastructure

Such social networks are necessary, but not sufficient, for lasting social change. Organizations are critical for providing the structure needed to sustain change. Over the years that Parks was with the NAACP, she and other activists learnt a great deal about responding to crises, public speaking, mobilizing people, the legal system, media, politics, and how to engage sympathetic whites. This provided the tools, infrastructure and experience essential to organizing and sustaining the year-long boycott, which involved thousands of individuals participating daily in an action that often came at a high personal cost.

The alternative is real

Parks and her fellow activists fought for an equality which they themselves had never experienced. However, a few months before the bus incident occurred, Parks attended the Highlander Folk School which trained activists in civil rights work opposing segregation. Participants were both black and white, and they worked and socialized together as equals. For the first time she experienced normal humanizing relations with whites. She left rejuvenated, understanding that the systemic changes she longed for were in fact viable. If the ideal feels unattainable, those who believe in it may give up fighting for it. Proof that the ideal is achievable strengthens change efforts.

Responsibility for the next generation

Parks was also driven by her sense of responsibility to others. Only months before a young black teenage girl had been abused when refusing to give up her seat on a bus, and Emmet Till had been brutally murdered, two incidents which deeply upset Parks. In addition she worked with youth, and strongly felt that adults, in their failure to stand up to segregation, had failed the next generation.

As the bus driver demanded she give up her seat, Parks realized she owed it to the young people to act according to her beliefs, and to stand up to segregation despite the risks.

Zigzagging towards justice

Rosa Parks’ story exemplifies the highs and lows facing anyone committed to addressing systemic social and political issues. The boycott eventually succeeded but a year later, unable to find a job, Parks and her family had to leave Montgomery. They moved to Detroit where the family’s financial woes still took years to improve. But she continued to be politically active, eventually working with Congressman John Conyers, always striving tirelessly to make and inspire change, until her death in 2005.

It is a bittersweet story when understood in full. For all the dramatic strides made since life under Jim Crow, black-white relations in today’s America remain fraught with significant problems. So much has been achieved, and yet there is so much more to be done.

But perhaps the problem lies, in part, with our expectations. A step forward is all too often followed by two steps back. Justice may finally win out – only to recede again. Or significant changes occur, but bring new problems that seem no less insurmountable.

Parks’ feet weren’t tired. She was just tired of giving in, and unwilling to give up. Deep social change depends on both individuals to take first action, and multitudes that join. Momentous events mobilise, but ongoing organised work sustains. Impatience drives, patience holds. Most importantly social change requires the belief that things could be otherwise, and that the responsibility to bring about something better lies with us.

(This article was first published in the Times of Israel)

Comments are closed.