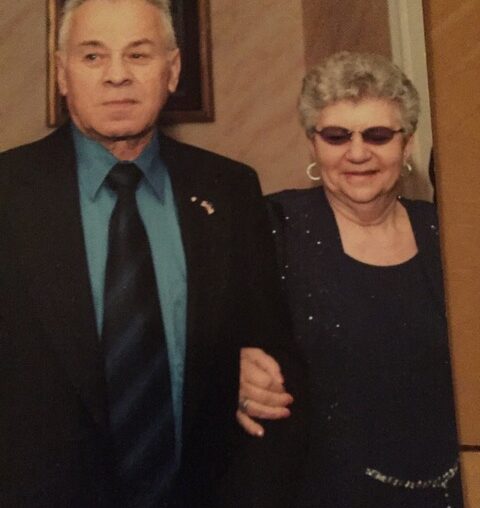

Two Polish Holocaust survivors from Poland. United by shared tragedies and strengthened by the love for the children they raised. Here is their story.

Yakov ‘Jacob’ Kazimierek, was born in Mlawa, Poland on December 10, 1926, one of the seven children of Abraham and Hannah (Granaska) Kazimierek. The family farmed and raised cattle, which they milked or slaughtered.

After Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939, thousands of the country’s Jews were subjected to the Nazis’ persecution, terror, and exploitation. Through the Nazi’s newly established “protective detention” orders, the Kazimierek family along with other Jews were forced to move to a Jewish ghetto. In 1942, the family were deported to Treblinka. Hannah and the four youngest children were immediately sent to the gas chambers.

Physically failing under the brutal demands of forced labor, Abraham was selected for murder in the gas chamber. Another brother, Hans, eventually succumbed to disease and malnutrition.

The two surviving brothers endured years of starvation diets, forced labor, and brutal beatings. ‘[Jacob] had to hide his food or others would take it and he would die,’ his cousin Regina Markowicz wrote in an account of his life. ‘He worked very hard and treated like an animal. He slept on a wood or cement slab and endured terrible winters without adequate clothing, bedding, or shoes.’ Jacob bore the physical signs of his imprisonment-scars on his back from the metal slats in his bed, one finger permanently disfigured from a beating, and of course, the tattoo number ‘76341,’ the number tattooed on his arm—on his body—for the rest of his life.

Shortly before the liberation of Auschwitz, Jacob managed to escape. Although the exact details vary in family lore—in one scenario, he escaped on a bicycle; in another telling, he and two friends escaped posing as Germans—Jacob spent the remainder of the war hiding in forests and cellars, subsisting on food foraged in the the woods, stolen, or given by kind Polish Christians. After Auschwitz was freed, Jacob was reunited with his brother Aaron, leaving them as the only two of nine members of the Kazimierek family to survive.

Sweden, a neutral country during the war, took in about 15,000 refugees. Jacob and Aaron were sent to a displaced persons’ camp in Jönköping, Sweden. Remembering the skills learned at his family’s home in Poland, Jacob worked in a slaughterhouse. In 1948, fleeing from a girlfriend who was pressing him into getting engaged, he moved to Israel and enlisted in Haganah, the Zionist paramilitary organization that fought for Israel’s independence. Four years later, he returned to Jönköping, where he met a twenty-three year old woman, a fellow Holocaust survivor whose story was as tragic and heartbreaking as Jacob’s.

The only child of a Jewish couple from Poland, Rachel Abromowitz Kazimierek was born on July 6, 1929. At the age of ten, she and her family were interred in the Lodz Ghetto. At the age of 13, she and her parents were among thousands of Jews deported to the concentration camps. After arriving at Auschwitz, she never saw her parents again. Rachel was placed in Bergen Belsen and assigned to work in the Wieliczka salt mines. Each day, she and other women were herded several miles each night, working in deplorable conditions underground. She was freed on April 15, 1945. Her years of forced labor would have serious impacts on her optical health.

Jacob, newly returned from Israel, and Rachel met at a dance in the displaced persons’ camp. According to their daughter Hannah Lewanowski, their match was not as much born of love as necessity. The United States gave preference to married refugees. The couple married in November 1952, and their first child Hannah was born thirteen months later. Jacob’s surviving brother, settled in Sweden, where he lived with his wife and three children until his death in 1979.

In 1954, Jacob, Rachel, and Hannah came to the United States, first settling in New Haven, Connecticut and then relocating to Waterbury. Initially working as a butcher at Bargain Food Center, he opened his own store, Brass City Beef in 1953, which he operated, with Rachel’s help, until his retirement in 1990.

In a March 15, 2015, an article in the Hartford Courant (‘Holocaust survivor built new life in Waterbury’), Jacob was praised for the store’s personal service and competitive prices. ‘He had a good following,’ said Tony Nardella, a former Waterbury police officer and customer. ‘He was well liked and always had a smile and a joke.’

‘He came to this country with no money,’ said Hannah. ‘He had no English. He worked seven days a week. He made it.’ The Kazimiereks developed a strong community with other Holocaust survivors. They socialized with each other, after sitting around a large table sharing schnapps and pastries while the children played together.

Meanwhile, Rachel continued to deal with eye infections, possibly a result of working in the mines. In 1961, she had her left eye surgically removed and was fitted with a prosthetic eye. In 1966, she had a detached retina, which resulted in loss in her right eye. From that time on, the children were cared for by a nanny. Determined, Rachel moved on with her life, using a cane to walk. Despite her initially limited English, Rachel volunteered at the local Easter Seals to help other visually impaired individuals and visited schools to share stories of her Holocaust experiences.

Jacob passed away in 2014. Rachel, 95, remains in the home she and Jacob originally purchased in Waterbury, Connecticut. She has 24-hour care but still prides herself in her independence and cognitive abilities. ‘My brain, sweetheart, is very clear and very good,’ she shared during a February 2025 interview. ‘I still remember birthdays and anniversaries,’ she said, rattling off the important dates of her children and grandchildren. Her daughter, Freida Winnick, who lives near by, provides additional support and care.

Rachel attends monthly Holocaust survivor luncheons in West Hartford, Connecticut. She also attends presentations organized by ‘Voices of Hope’, a non-profit educational organization created by descendants of Holocaust survivors from across Connecticut to raise social awareness.

Rachel emphasizes that she holds no ill will despite her history. ‘I am not against anyone,’ she said. ‘I get along with everybody.’

1 Comment

Such a wonderful story about Rachel and Jacob.

Thank you, Marilyn!

Sharon Easton; Storyteller, Writer

Beach Moose & Amber: Finding My Jewish History

Writer’s Union of Canada, Canadian Writers Association, The Federation of BC Writers, and Around Town Tellers Nanaimo

Website: https://www.sharoneaston.com

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/sharoneastonauthor