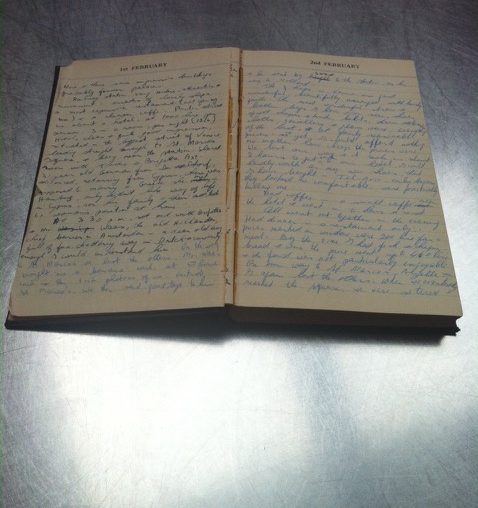

My sister and I never expected to find Naomi’s diary. Indeed, for many years, we did not even know of its existence. A non-descript, navy-bound volume, it had been stashed away in a drawer of the massive wooden study desk, at which our late mother had worked as an academic economist for so many years. Perhaps she had simply forgotten writing it? Or perhaps she had chosen not to share her youthful passions and agonies, hopes and fears with her two daughters? We will never know. I had long abandoned any hope of uncovering more details of my mother’s past, her memories having been gradually extinguished by Alzheimer’s disease, which had afflicted her for the last decade of her life. Now, 60 years later, as I turn the diary’s yellowed pages filled with her distinctive script, I feel grateful for the opportunity to discover her anew, albeit in a younger form, becoming acquainted with the person she once was before I was born.

So begins the Preface of my recently published book, Unlocking the Past: Stories From My Mother’s Diary. Written in English in the mid-1950s, when a postgraduate scholarship had taken her back from Australia to her birthplace of Israel after almost a decade’s absence, the diary provides a glimpse of what life was like then for a still single, late 20-something woman – a highly unusual phenomenon for that time. Attractive and bright, Naomi was courted by a host of mostly unsuitable admirers, although occasionally, one would become the focus of her hopes and dreams. After all, as she notes, her mother had advised her to “secure a future” for herself, urging her to work hard to accomplish her purpose: in other words, “get married”.

Part-travelogue and part-social commentary, the diary reads like a film script, the vividly portrayed characters flitting in and out of various settings in Tel Aviv, Jaffa, Jerusalem and Ashkelon. One moment my mother is at a party or concert, describing the dating scene: “Noticed some very good looking men in the audience. Wonder where they usually hide.” The next, she is on a crowded bus, discussing the four young Yemenite girls seated behind her: “Probably recent arrivals to the country. Full of joy of life, laughing and continuously talking in high pitched voices, cracking small black seeds and throwing shells on the floor of the bus.”

A picture builds of what life was like in the then recently established State of Israel as seen through the eyes of a former Sabra, who has become somewhat of a stranger in her own land. Many of those Naomi meets are keen to move elsewhere, struggling with the harsh daily existence they face and believing there to be more opportunity overseas. A certain unease lurks behind the pages too, and on one occasion, she even has to identify a suspect at the police station after an elderly woman is raped across the street from her mother’s home in south Tel Aviv. More often, however, she is scared to walk alone in isolated areas, having heard about, as she puts it, “some unpleasant and unfortunate encounters with Arab infiltrators”. “Infiltrator” – a term recently revived to denote African asylum seekers in Israel was the word used to refer to citizens of surrounding Arab states, as well as Palestinians, who had entered Israel illegally, especially if they were armed or had committed crimes against people or property.

Emotions certainly ran high within Israel itself too. On a morning walk through the Carmel market near the family home in south Tel Aviv, Naomi describes police arresting an “old Arab who was selling baskets… He was yelling his protests. Bystanders said he was allowed to sell his products in the main street, but not in the market. Further on I heard terrible cries, saw a young fellow who had slashed his own throat in protest at having had his cart full of vegetables taken to the police station. Apparently, he too had no permit to trade in the market.”

Keen to share my wonderful discovery, I wrote a story about the diary and submitted it to an online Jewish literary journal. Concerned, however, that the excerpts I had provided were a little short and unfulfilling to the reader, the New York-based editors suggested instead that I expand an entry or two to make it the focus of the piece, as well as a complete, stand-alone story. That particular journal publishes three genres of creative writing – fiction, creative non-fiction and poetry. I did not want to fictionalise my mother’s diary. So what exactly is creative non-fiction and would I be able to produce a story in that genre based on the diary?

Having begun my writing career in academia, I had later switched to journalism, working for a Jewish community newspaper. Since then, I have continued to fine-tune my editing skills and have kept on writing articles, essays, whether personal or not, memoir… but creative non-fiction was a new challenge. American writer Lee Gutkind, who is known as “the godfather behind creative non-fiction”, defines the genre as “true stories well told”. In other words, the writer produces factually accurate prose about real people and events in a compelling, vivid and dramatic way. As he puts it, “the goal is to make nonfiction stories read like fiction so that your readers are as enthralled by fact as they are by fantasy”.

And so I embarked on a quest to learn how to write creative non-fiction, teaching myself to write in scenes. I have found creative nonfiction to be liberating in that it enables the writer to use literary or fictional techniques, such as description, dialogue, and point of view, striving to immerse writer and reader alike in the action so that we are able to picture what life in Israel must have been like for my mother at that time. In so doing, I have turned Naomi into a character in her own story, changing it from first to third person.

In the process of writing this book, I learned a great deal about Israel in the early days of the State. For my work entailed interspersing my mother’s personal experience with historical facts where it is crucial to be accurate. It was often like putting a puzzle together, one piece at a time. So I read widely, researching everything from how Israelis dressed and behaved on buses, at the cinema and at parties in 1950s’ Tel Aviv and how Yom Ha’azmaut (Israel’s Independence Day) was celebrated and development towns like Ashkelon were established.

I read about Arabs fleeing Jaffa in 1948 and about how until 1967 an armoured truck would make the trip along the one perilous road connecting the Jewish part of divided Jerusalem to Mount Scopus, with only a small slit across the window in front of the driver’s seat to see what was directly in front. Books about 1950s Israeli social history were particularly pertinent to my research, while other sources included films, newspapers, music, novels, even Google maps … there was an abundance of enriching resources available.

Along the way, I was helped by many, from the former owner of the Dagon Inn, one of the first hotels in the South, who painted such a vivid picture of the Ashkelon of his childhood for me to the archivist from the Cameri Theater in Tel Aviv, who provided me with photos and programs from the era.

I now count my mother’s diary as among my most cherished possessions. After all, it provides a portrait of Naomi as I never knew her: a young passionate woman searching for intelligent companionship and the man of her dreams. At the same time, and especially in the wake of the most recent deterioration in relations between Israel and the Palestinians, it is sobering to read a personal account of the early trials and tribulations, anguish and vulnerability of the new State of Israel. Using the key afforded to me by creative nonfiction, I have tried to recreate the Israel of my mother’s youth, unlocking a part of her past with which I was unfamiliar, a past that I thought had been lost forever.

Unlocking the Past: Stories From My Mother’s Diary is available on Amazon as an e-book or paperback or from www.mazopub.com

Comments are closed.