On the museum wall, a black and red painting is displayed. It depicts monsters with breasts, penises and anguished faces, as well as human body parts, frogs and serpents—all engulfed with flames. A hellish landscape that echoes the works of Hieronymus Bosch and August Rodin. I look closely at one of the monstrous creatures. It sucks a large penis, one of several that erect from another creature, while its face expresses boredom. This monster has the facial expression of a jaded worker in a factory, or a tired cashier in a supermarket. I imagine it saying, “Ugh, another dick to suck” or “When is this shift ending?”, and I smile at it.

In Keith Haring’s exhibition Art Is for Every Body at the AGO in Toronto I am delighted by the combination of humour and cultural criticism. Although it echoes Bosch and Rodin, this canvas does not warn people of what they should expect after death but rather points to the hell we experience in this world. The half-angel half-needle creatures flying upward, for example, might refer to the high drug use on the streets of New York City during the years Haring lived and worked in it until he died in 1990. But Haring’s art strikes me, most of all, because it seems highly relevant for 2024 and the ongoing conflict between Israel, my home country, and Gaza.

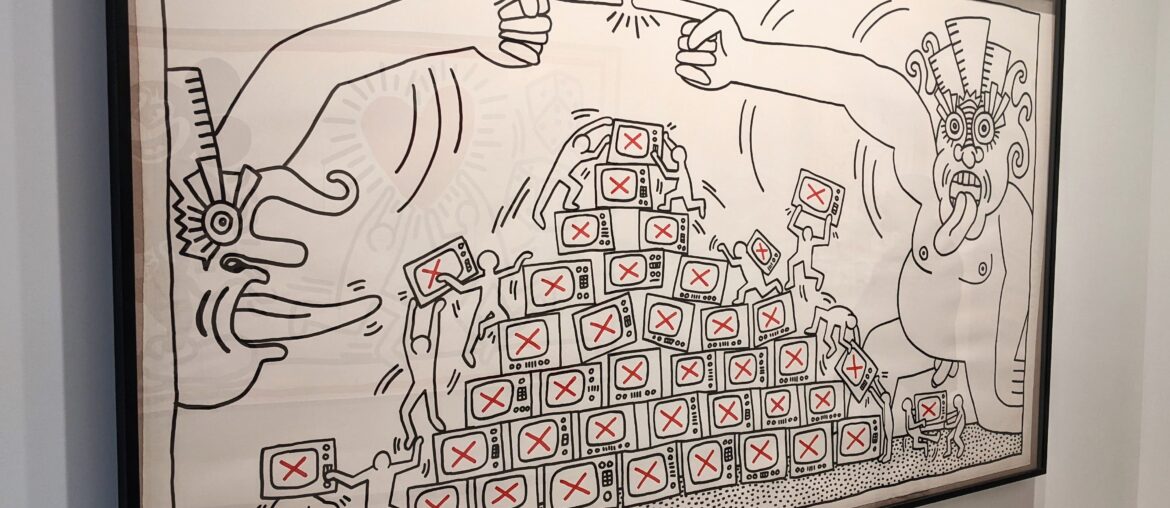

Another work that shows devilish monsters is made almost entirely of black lines over a white canvas. The two outlined monsters—large round eyes, long fleshy tongues, protruding noses, and crowns that look like school rulers—are pointing at each other. Their fingers are almost touching, like the fingers of God and Adam in Michaelangelo’s famous fresco. But here, the monsters bring each other to life or accuse one another. Or maybe both at the same time. Under the monsters’ hands, televisions marked with red Xs are carried by people and piled into a pyramid.

Haring’s art is clear yet ambiguous, full of symbols yet open for interpretation. In this painting, for example, surely the artist wanted to criticize American politics and mass media in the 1980s. Or perhaps he aimed to say something about the patriarchal society since the creature on the right has a penis dangling between its legs. Maybe this is a work about the new opium that desensitizes people—television. In any case, the monsters look ghoulish but also ridiculous as if they dressed up as scary creatures rather than being genuinely intimidating. Haring disarms them from their monstrosity by making them laughable, just as he did in the previous work.

No one interpretation is correct, and standing in front of the canvas, I see more meanings emerge. As an Israeli, I am very concerned with the situation in my country, and even though I’ve been living in Toronto for the past decade, my mind is occupied with the current war. No wonder I see the monsters as representing Israel and Hamas, or more precisely, Netanyahu and Sinwar. It has been more than ten months since the traumatic attack of Hamas on Israeli citizens on October 7th, 2023, the hostages are still kept in the Gaza Strip, and the war in Gaza takes a toll on innocent Palestinians. Israel and Hamas, like the monsters in the painting, point fingers at each other, and each blames the other for the terrible situation. But more than just blaming, each has created a monstrosity on the other side. By acting violently, more violence is evoked. One may assume extremists on both sides have conflicting interests, but looking at this canvas, the mutual interest becomes clearer—the desire to destroy in order to build a new country based on fundamentalist religious values. The figures piling on television sets are enslaved to the dictators, Netanyahu and Sinwar, and to the conception that they are at war with their enemy. But in fact, the monsters from within are the ones that oppress them.

In another piece, Anti-Nuclear Rally (1982), a baby surrounded by angels arrives in heaven on a cloud, but the cloud is made out of a nuclear explosion shaped like a mushroom. In the lower panel, a pyramid person, or perhaps a god, with the nuclear concentric elliptic symbol on its chest, is being climbed on from both sides by people holding sticks or swords. Haring is probably alluding to the Cold War, but I see the conflict between Israel and Iran, which is one of the largest funding resources of Hamas and a constant nuclear threat to Israel. Last April, Iran launched 300 missiles and suicide drones at Israel in an attack that could’ve easily become the beginning of a third world war. The swords raised in each figure in Haring’s poster leave hardly any room for imagination—the leaders of two patriarchic countries and cultures compare who has a bigger phallus. I cannot hold myself from thinking about “Sword of Iron,” the name Israel had given to the current war with Gaza, which like previous operations names—Pillar of Defense, The Guardian of the Walls, and The Protective Edge—provoke a violent combination of power and masculinity. In fact, the word Zayin in Hebrew denotes both weapon and penis.

This point becomes especially viable when I see a large panel in the shape of a pink penis, titled The Great White Way (1988). In its centre, stands a god-like figure with limbs stretched into a cross, a dollar sign on its chest and a large erection between its legs. Smaller human figures worship and climb on it and two hold its crown. The painting is dense with figures and symbols, including weapons and war vehicles. Haring depicts and criticizes the “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” as worded by the author bell hooks who is quoted on the plaque. Serious as it is, Haring’s painting is full of funny details, such as laughing pigs and a figure with a double penis.

It’s not easy to find hope for a better world these days, but exiting the exhibition I come out with a lighter heart. It was a joy to take the time to visit the exhibition, to wander between the humorous pieces, and to challenge my thoughts and ideas. Perhaps monsters will always be part of this world, but also art, joy and laughter.